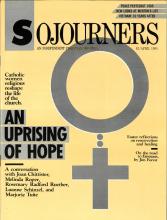

Easter is a season of resurrection and hope. At Sojourners, when we have looked around for signs of hope, the witness of Catholic women religious has often been prominent in our view.

Religious sisters are at the center of the most hopeful initiatives for change in this country. They are praying for justice and marching for peace, advocating for women and standing with the poor. And out of their experience of oppression as women and their bonds as sisters, they are forging a new spirituality.

With an authority that comes from their experience of God, of the poor, and of community, Catholic women religious are revolutionizing the church and forcing an institution that does not recognize their authority to examine itself and its life. While they have a particular message to the Roman Catholic church, what these sisters have to say offers hope and challenge much more broadly to all of us in the churches.

It seems fitting this season to bring together some of the women who are at the heart of this movement of empowerment and hope. On the following pages is a conversation with four religious sisters and a Catholic lay theologian that took place at Sojourners.

—The Editors

Sojourners: New roles and new leadership appear to be emerging among religious women. What is happening, and is this really new?

Joan Chittister: Radicalism has been at the base of the history of religious communities for centuries. I would simply argue that the old radicalism has become establishment.

Read the Full Article