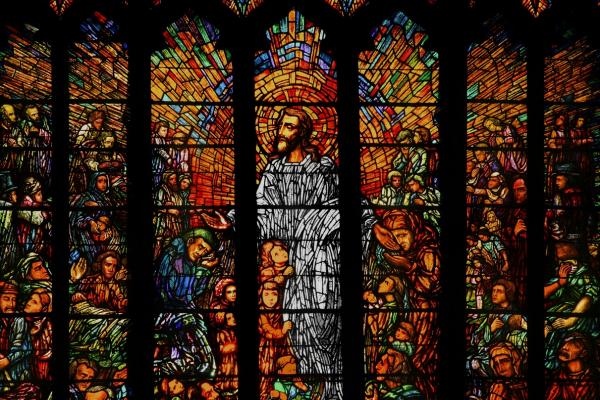

THE SUNDAY AFTER EASTER we all take a breath. We’ve worked hard to offer our best for Easter. Ministers often have had to preach more than our accustomed once a week. Choirs have gone all out. The sanctuary has been cleaned and decorated and trampled upon and cleaned again. Worship services may even have been lively and full. Now, as the Easter season settles in, all goes back to normal. We gather these Sundays not for spectacle, but for the risen Christ, refracted off the faces of one another.

The lectionary readings send us into unfamiliar territory. During these days, there’s not an Old Testament reading in sight—the book of Acts functions as the history of God’s faithfulness. Revelation tears a hole where Paul usually is. The gospel texts speak to the unbearable newness of a risen Lord reorienting the world around himself.

In the ancient church, those baptized at the Easter vigil would first be stripped naked before going under the water. They then donned a new robe as a sign of “putting on” Christ—and wore it throughout the Easter season. They went to church daily, learning what it meant to be “in Christ.” Had they ever seen a baptism before attending their own? Had they ever shared in Eucharist until they tasted one? I wonder whether the Easter season can be a new normal. Not one where we settle for the ordinary, but one where we take part in the risen Christ’s wrapping of all reality around the empty tomb.

Read the Full Article