THERE ARE TWO churches in Newton County, Miss., that bear the name “Good Hope.” The first, Good Hope Baptist Church, was founded by white slaveholders in the 1850s. At least 20 African Americans were members of that church, forced to worship God alongside those who kept them enslaved. After the Civil War, Black members of the church banded together to form an independent community, the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope. One of their first goals as emancipated people was to establish a church of their own. Against immeasurable odds, they founded Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in 1908. But that same year, terror threatened to rip the nascent community apart. Three congregants—William Fielder, Dee Dawkins, and Frank Johnson—were brutally tortured and lynched by a mob of at least 50 white men. The three were targeted for being associated with a Black sharecropper accused of killing his white employer. The mob went on to wreak havoc on Black neighborhoods. Traumatized by the violence and faced with restrictive Black codes that preserved white supremacy in the South, many members of the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope fled north.

But their families’ connection to that sacred ground didn’t waver. For more than 100 years, on the first Saturday in August their descendants have travelled from across the U.S. to the church for a revival. They sing, pray, and gather for a fish fry and soul food. They share news about marriages, births, and deaths. They listen to sermons and care for the cemetery where their ancestors are buried. And most importantly, they remember.

tulsa_marker2.png

Last August, descendants gathered at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Newton County for another reason: to unveil a historical marker honoring the memories of Fielder, Dawkins, and Johnson. The marker describes the terror that was unleashed on their community and the failure of local law enforcement to hold anyone accountable for the deaths and the destruction of Black property. Darrell Fielder, the great-great-grandson of William Fielder, told Sojourners he believes Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church was the appropriate space for “resurrecting” the legacies of these three victims. “It is the one space where Black people could practice a liberating faith and speak in frank terms about injustices,” Fielder said. “In placing these markers on church ground, we are honoring these martyrs and letting them know that God was always with them.”

The historical marker at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church is part of a nationwide effort to acknowledge the racial violence embedded in U.S. history—and to examine how that legacy has shaped the present. Launched by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an Alabama-based nonprofit, the Community Remembrance Project (CRP) has helped communities install more than 65 historical markers honoring lynching victims. In many of these locations, people of faith have been deeply involved in raising awareness and building diverse coalitions to tell the truth about the past.

Joyce Salter Johnson, 82, was born on the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope and baptized in a little pond behind the church. Inspired by the verse from Proverbs instructing people to “not forsake your friend or the friend of your parent” (27:10), Salter Johnson, a descendant of Frank Johnson, has spent 40 years piecing together the history of the families of the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope. In 2017, she published a book,The Freedmen Settlement of Good Hope Mississippi: The Beginning, drawing from church records, journal entries, census data, wills and other documents, and interviews with descendants. After hearing about the EJI project, Salter Johnson convened a neighborhood coalition to install the historical marker. It was a coalition so wide that it even included members of what Salter Johnson calls the “white Good Hope Church.” Salter Johnson told Sojourners she hopes this effort will inspire communities to work together toward “justice for all.”

curtis_fielder.png

“We can help ensure that such tragedies do not exist as we move forward in the 21st century with great challenges and a tremendous need for strong and creative leaders,” Salter Johnson said. “It can help move our communities toward reconciliation of our past and present.”

Facing the past

IN THE YEARS that followed the Civil War, white communities in the South used violent, public acts of torture to terrorize, humiliate, and control newly emancipated African Americans and their neighborhoods. Black Southerners were lynched for resisting economic exploitation, for trumped-up allegations of criminal activity, for perceived violations of white supremacist social norms—or for merely being associated with someone who was rumored to have done these things. White mobs seized people from jails and courtrooms without fear of repercussion, since local officials of the time often tolerated or condoned these attacks and failed to hold perpetrators accountable for their crimes. Nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings occurred across 26 states between 1865 and 1950, according to EJI. In addition to the loss of life, these extrajudicial killings had the effect of enforcing racial segregation and preserving the ideology of white supremacy.

Black churches became powerful sites for organizing and activism, including Warren Temple United Methodist Church in LaGrange, Ga. On Sept. 7, 1940, a young man named Austin Callaway was thrown in LaGrange’s city jail. A band of armed white men snatched Callaway out of the jail, shot him repeatedly, and left him to die on a rural road. The reasons for Callaway’s arrest are unclear. No police records exist that describe the allegations, and the police failed to publish an investigative report on his murder.

Rev. L.W. Strickland, who was pastor of Warren Temple UMC at the time, tried to draw attention to the crime, establishing a local chapter of the NAACP to bring together community members for mass meetings. Although Callaway’s murderers were never held accountable for their crime, Strickland’s activism had an enduring impact. Years later, in 2017, community leaders installed a historical marker at Warren Temple UMC honoring victims of lynching in Troup County, Ga., including Callaway. Rev. Carl Von Epps, current pastor and lifelong member of Warren Temple UMC, told Sojourners the marker is part of a yearslong, multipronged effort in LaGrange to acknowledge the failures of the past and chart a new way forward. The activism of local leaders led LaGrange’s mayor and police chief to apologize for their predecessors’ complicity in Callaway’s lynching. The police chief also implemented reforms to prevent fatal police shootings of Black residents, though reports of discrimination and unjust punishment in LaGrange persist.

As someone who grew up in LaGrange and graduated from a segregated high school, Epps, 73, said he can’t see the profound changes occurring in his city as “anything other than a movement of God”—and the church has faithfully worked to advance that movement. “I think we have been representative of a community church and that’s what we still try to be,” he said. “It gives us pride knowing that we are making a difference in our community.”

A concerted effort

GETTING THE WIDER community on board with installing a marker is not always easy. In Tallahassee, Fla., faith leaders from three congregations joined forces to start a coalition in the area—St. John’s Episcopal Church and First Presbyterian Church, two predominantly white congregations, and St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church, which is predominantly Black. When leaders first presented the idea, they encountered some resistance from within their own congregations and from Black leaders in the wider Tallahassee community. Some opponents to the project were concerned that the subject was too hurtful to be remembered, according to J. Byron Greene, an African American native of Tallahassee and a member of St. Michael and All Angels. “I believe that the subject matter, lynching atrocities, is one component of the larger issue of racial degradation which still remains like [a] sore on your knee,” he told Sojourners. “Engaging in a project like the [Community Remembrance Project] can be akin to breaking the scab.”

dee_dawkins.png

The coalition created public forums where community members could learn more about the project, Greene said. EJI was brought in to help answer the community’s questions and the coalition eventually grew to include a wide array of groups, including several predominantly African American local churches, as well as Jewish organizations, a Buddhist center, and Ile Asho Funfun, a community dedicated to the Yoruban deity Obatala. While many of the people who attended the marker installation ceremony held this past July were African American, the majority were white, Greene said, which he found encouraging. “In my opinion, the act of remembrance is twofold,” he said. “It is an act to re-member, meaning to come together again ... and it is an act of repentance, more clearly, an act of turning back to God and committing to living out the covenant of ‘loving our neighbor as ourselves.’ ... If we are not mindful of our common humanity, these types of atrocities can surely happen again.”

The same scene

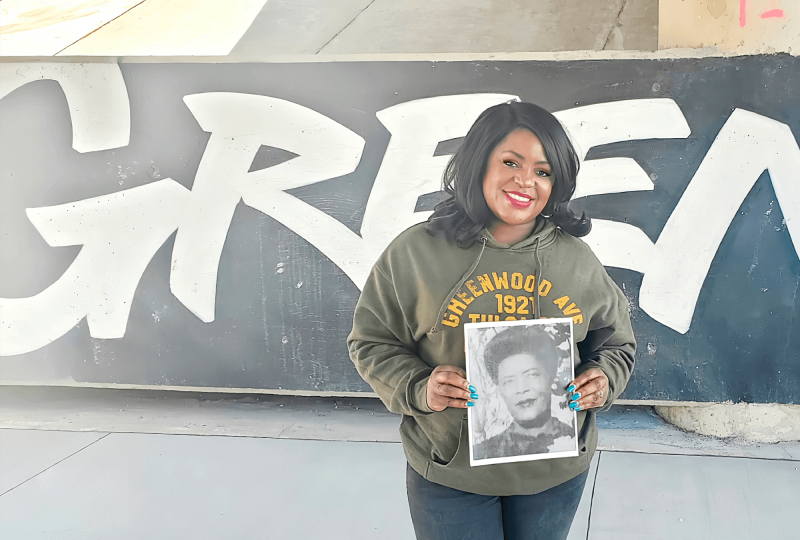

IN 1921, A young woman named Rebecca Brown Crutcher and her husband owned a thriving barbecue restaurant in Greenwood, a prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa, Okla. The couple had chosen a prime spot for their business, right near the train station in the heart of their beloved community.

Their lives were disrupted in late May of that year when a white mob tore through Greenwood, murdering as many as 300 residents. While the Tulsa Police Department chose to ignore the violence—and in some cases, joined in—the mob burned Black homes, places of worship, and businesses. Crutcher and her family fled for their lives on the back of a truck, leaving their business and home behind. Like many survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Crutcher rarely spoke about the terror she experienced that day, fearful of retribution from white people. But after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., she told her grandson for the very first time that, “Something like that happened here, too.” Even then, decades later, Crutcher could only speak about it in a low whisper.

tulsa_massacre.png

Though the massacre had profound effects on her family and her hometown, Tiffany Crutcher, Rebecca Brown Crutcher’s great-granddaughter, never learned about the tragedy while attending Tulsa schools. As a child, she played on the grounds of Vernon AME Church, the only structure to have survived the massacre, but had no knowledge of its history. It wasn’t until Tiffany Crutcher got to college that she learned about the destruction of “Black Wall Street.”

Then, in 2016, a police officer shot and killed Tiffany’s twin brother, Terence Crutcher. The Tulsa officer, a white woman, was later acquitted of manslaughter. Tiffany Crutcher was stunned by the parallels she saw between the lives of her brother and great-grandmother, and the fact that the fear her great-grandmother had felt back in 1921 appeared to have been passed down through the generations. “I often just wonder in my mind, how she was feeling, what she was thinking, running away from terror. And I’m thinking about my brother, what he was thinking as a mob of police officers ran toward him,” Tiffany Crutcher told Sojourners. “It seems like the same scene.”

After her brother’s death, Tiffany Crutcher pledged to fight for the justice denied to her family. She started a foundation that advocates for criminal justice and police reform. As part of her outreach, she decided to bring Tulsa community leaders together to create a memorial for victims and survivors of the Tulsa massacre. Last year, the Tulsa Community Remembrance Coalition unveiled a historical marker outside of Vernon AME Church that describes the events leading up to the massacre, pinpoints how law enforcement failed to protect Greenwood residents, and details the displacement of more than 10,000 Black people. “If we don’t learn about what happened or know about our history, we’re doomed to repeat it,” Tiffany Crutcher said.

tiffany_crutcher.png

One of the major goals of the Community Remembrance Project is to help people see the connections between racial violence in the past, present, and future, Kiara Boone, EJI’s deputy director of community, told Sojourners. “If we do the hard work of truth telling, confronting, documenting, understanding what has happened, then we’ll be in a much better position to implement reforms and solutions that are actually reparatory and that get us to the more just and equitable world which we seek.”

As coalitions coalesce, they engage with their communities by organizing educational and memorial events such as racial justice essay contests for local high school students and soil collection ceremonies at or near lynching sites, the jars of which are then displayed in local exhibits and at EJI’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Ala. When deciding where to place historical markers, the coalitions often gravitate toward central, heavily trafficked locations. In many rural communities, that central location is often a church, Boone said. Seven such markers have been placed on or near church grounds.

As a Christian, Tiffany Crutcher said she believes “remembrance work is a radical act of love.” For her, honoring the God-given dignity of lynching victims, remembering their extraordinary faith and resilience, and reminding Black children today that greatness is embedded in their lineage are all steps toward justice. “When our stories and legacies have been silenced for far too long, to be able to right those wrongs and to honor and remember, that’s where justice lies.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!