For you know how generous our Lord Jesus Christ has been: he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that through his poverty you might become rich. (2 Corinthians 8:9)

Such a powerful and beautiful statement comes to us in the midst of prosaic instruction about finances in the life of the church. Paul takes us from the ordinary problems of daily life in the Christian fellowship and plunges us into the heights of poetry and the depths of theology.

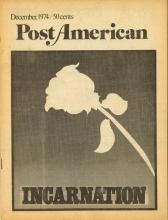

Paul is not just leaving the mundane in order to have a refreshing aesthetic jump into spirituality. He is not just giving us a beautiful truth without consequences; he is, rather, telling us that the sublimity of the incarnation shows a pattern of action to be imitated by the Christian today.

"You know," says Paul. The Corinthians knew that he who was rich became poor for their sake. To begin with, those who had not been able to see Jesus in Galilee received his message from those who could honestly say, "Poor ourselves, we bring wealth to many; penniless, we own the world" (2 Corinthians 6:10). Just like Jesus, they too had a lifestyle marked by real poverty.

Read the Full Article