“THIS TIFFANY stained glass window was donated by parishioners in honor of Jefferson Davis,” said our guide, Barbara Holley. Holley is a member of the “history and reconciliation initiative” at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Va. St. Paul’s, located across the street from the Virginia general assembly and around the corner from the Confederate White House, was called “the Cathedral of the Confederacy” for a reason (see "Robert E. Lee Worshipped Here: A Southern church wrestles with its Confederate history," by Betsy Shirley, in the April 2017 issue of Sojourners).

Fragments of stained glass honor Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Gen. Robert E. Lee. Both men gleaned inspiration, comfort, and resources for their cause here. Their pews are marked with commemorative plaques.

A diverse group of historians and St. Paul’s parishioners, led by chair Linda Armstrong, has worked methodically for a year and a half to unearth the artifacts of white supremacy preserved in the church’s windows, pews, sermons, vestry rolls, and minutes of meetings. They discovered documents that confirm St. Paul’s vestry members were among the original architects of the Confederacy, the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow in Virginia, and 20th century redlining.

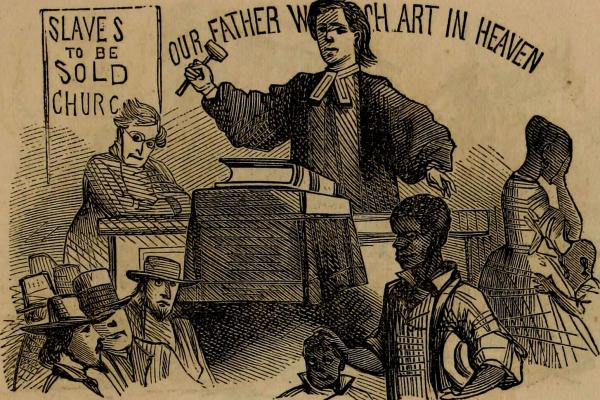

Think about that: The architecture of white supremacy in the U.S. was literally crafted in and by the church. Only now are we beginning to piece together the stained and distorted fragments of our history; intentionally broken, twisted, and erased from common memory. Amnesia and conflicts of memory render us vulnerable to manipulation. Thus, common memory is essential for peace.

THE VERY FOUNDING of Richmond has its roots in domination. In 1734, the Virginia House of Burgesses asked Virginia planter and surveyor William Byrd II to plan a town. Byrd, justified by the 15th century “Doctrine of Discovery,” claimed land at the falls of the James River and named it after similar land in London. The spirit of colonization claimed dominion on that day. It declared exclusive right to rule and demanded the exploitation or extinction of the other. Then as now, the construct of race was a tool of colonization, a mechanism used to claim, protect, and preserve power.

Over the next century, as Benjamin Campbell explains in Richmond’s Unhealed History, Richmond grew into the second largest slave market in the U.S. And while the Civil War and Reconstruction presented formidable challenges to white dominion, the backlash was fierce.

In 1888, Benjamin Harrison, a former Union Army colonel, defeated incumbent president Grover Cleveland, an anti-Reconstruction Democrat. Months later a Confederate association formed in Richmond and began construction of a monument to Confederate soldiers and sailors. Two years later, a statue of Robert E. Lee was installed on what became Richmond’s “Monument Avenue.” Over the next five years, according to the group Monroe Work Today, white Virginians lynched 34 African-American men—a 340 percent rise in lynchings over the previous five years. Backlash against Harrison’s attempts to protect African-American voting rights helped set the stage for Cleveland to win back the presidency in the next election. The monument to Confederate soldiers and sailors was established at the highest point in Richmond, atop a Native American burial ground, months after Cleveland was sworn in for the second time. For a time, the rage to protect white supremacy was mollified. Lynchings in Virginia dropped to six over the next five years—an 82 percent decline. Murder is less necessary to protect power when law and policy will do the bidding.

The civil rights movement chipped away at the 20th century white supremacist infrastructure, but it did not tear it down. Eradication will require common memory, common interrogation of colonizing theologies, and common courage to dream together of a new way of being in the world.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!