HANNAH ARENDT SAID we can ask of life, even in the darkest of times, a “redemptive element,” and art can be that—an affirmation of right, light, truth, some beleaguered beauty. But note well: Art is no escape from the problems of the world but, rather, a repurposing, a resistance. And, of course, this phenomenon of violence into art can go both ways. Michelangelo’s bronzes, including his colossal papal statue of Pope Julius II, were melted down into cannons and other weapons during the French Revolution. It’s our choice.

Here are four artists who chose to turn trauma—civil war, natural disasters, apartheid, and female genital mutilation—into sights to behold.

Ralph Ziman, South Africa

AN IRONCLAD BEAST—bulletproof, 10 tons of hardened steel, its 165-horsepower engine roaring at high speeds down narrow streets of black townships, demolishing obstacles in its path and stinking of diesel fuel—has been resymbolized into a masterpiece, embossed with 55 to 60 million multicolored African trade beads, a total change in form and function.

zimanonlineedit.png

Designed and put into service in apartheid South Africa in the 1980s, the so-called Casspir, a mine-resistant and ambush-protected vehicle, has been subverted. Says South African artist Ralph Ziman: “The Africanization of the Casspir seemed to take away the terror it once evoked ... people felt comfortable to approach it, touch it, and share their stories and memories.” He elaborates on his intention: “To make this weapon of war, this ultimate symbol of oppressing ... to reclaim it, to own it, make it African, make it beautiful, make it shine.”

Born in South Africa in 1963, Ziman grew up in a strict system of institutionalized racial segregation and political and economic discrimination—“apartheid,” which translates in Afrikaans to “apartness.”

“I have vivid memories,” he says of his first sighting of a Casspir. It was April 1993. Charismatic leader Chris Hani had been gunned down outside his house in a Johannesburg suburb by a white nationalist. The artist drove to the funeral and saw columns of Casspirs descending the dusty streets; heavily armed police fired tear gas, shotguns, and automatic weapons. More of the same occurred the next day in Soweto, where police and army units parked their Casspirs along the highway and exchanged gunfire with members of the African National Congress. “Tear gas and smoke burned our eyes and into our memories, along with the sight of armed men on the Casspirs ... for me, covering this beast with beads is catharsis,” says Ziman.

Every single bead of the millions used had to be threaded by hand. The artist used commercially available colors and a computer to create a 3D model of a Casspir, which he flattened to design segmented coverings with traditional African patterns evolved from body painting, mural art, and weaving. The patterns were farmed out to several dozen Ndebele women, who for generations have been South African beading specialists. Most of the wiring was done by Shona men from Zimbabwe.

It took the team of 60 people, working 12-hour days, six days a week for six months, to cover all the surfaces in elaborate panels of brightly colored glass—even the hubcaps, steering wheel, and headlights. Pressure built to finish in time for the debut at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, requiring long hours into the night. On the last day, a group of Zulu women wore traditional dress and serenaded the Casspir as it drove away.

Sana Musasama, Sierra Leone

THE SERIES IS called “Unspeakable,” not in the sense of avoidance of something too horrible to address, but rather a silent understanding that makes speech unnecessary. Sana Musasama’s ceramic pieces reflect on the practice of female genital mutilation, which she refers to as “excision,” part of her protectiveness of cultural differences. Excision is closer to the more commonly used term “cut,” she explains, a practice she learned about in the 1970s while living in a Mende village in Sierra Leone. It was only in retrospect that she came to comprehend a concept that has preoccupied her creativity since 1995.

musasamaonlineedit.png

Multicolored and in mixed media, with components ranging in size from 6 to 14 inches long, the installation of around 100 examples of female genitalia on her studio wall defies the cliché of variations on a theme. Musasama’s symbolically rich ceramics include cloth and metal, fiber and paper, gold leaf and organic bark. They feature doorknobs to unlock the womb; spikes, rods, and chains preventive against rape; needles suggesting stitching that can be involved in the procedure; shielding hands and mummified wrappings for healing; protruding eggs and ovaries bespeaking fertility; snaking and tied-up accumulations of scar tissue; and on and on.

“Cutting” is now prohibited in several African countries and elsewhere because of medical risks and complications for sex, childbirth, and other reasons. The procedure spans from a few, small, quick nicks to a far more radical removal of labia, clitoris, and surrounding vulva tissue. It became a hot topic in the 1990s, when Musasama came to understand what happened in Sierra Leone in the 1970s.

Musasama, who is African American, was traveling in West Africa in 1975 when she met a guide in Ghana who invited her to his home village in Sierra Leone. She remained for more than nine months and says she developed a sisterhood with a group of 10-to-15-year-old girls who visited her daily. They combed her hair; tried on her clothes and makeup; and taught her formal greetings in Mende and how to properly sit and eat with her tongue, never allowing food to touch her lips, as well as how to cook on three rocks and wash clothes in the river; how to dance and sing their songs as well as birth and death chants; and how to farm, fish, and repair her clay hut and oven, and more.

Suddenly one morning there were no young girls in the village. They returned 13 weeks later—changed. “Our ritual of sisterhood was no more,” Musasama laments. “They no longer had the sparkle of wonderment in their eyes; they weren’t silly young girls any longer. They didn’t want to have anything to do with me.” She didn’t understand their newfound gravitas until much later. They had been initiated into their lives as mature women, prepared for marriage and motherhood, and that included “excision.”

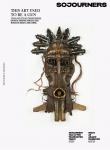

Gonçalo Mabunda, Mozambique

GONÇALO MABUNDA'S ART materials are, to say the least, unusual: Kalashnikovs (AK-47s), rockets and their launchers, pistols, shell casings—remnants of ordnance from a 16-year civil war largely fought against Mozambique’s civilians. In a word, there was “savagery”: mass killing, forced labor, child soldiers, rape, and famine. In a population of 13 to 15 million, 1 million died, another 5.7 million were internally displaced, and 1.7 million became refugees.

Mabunda was 2 years old when the civil war started in 1977, and he has frightening memories of soldiers roaming around, dripping in arms—especially at night. He remembers being impressed by his uncle’s AK-47, which he was allowed to hold.

mabundaonlineedit.png

The war ended in 1992. Later, the Christian Council of Mozambique started a project called “Transforming Guns into Hoes,” inspired by the verse from Isaiah: “They will hammer their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks.” A remarkable 800,000 weapons were collected.

Already working in metal, Mabunda was one of 10 artists invited to use the decommissioned arms as art materials, and, to honor all victims, he aimed to incorporate all the kinds of weapons used in the war. His spectacular throne chair series, for which he is most recognized, began innocently enough: He needed a chair while working; afterward, someone came along and wanted to buy it. Then he conceptualized a “throne” laden with irony, referencing African leaders placing themselves in positions of hereditary kingship, holding unto power by force if necessary, a national as well as tribal phenomenon. Yet another variation on African traditions: His wall portraits anthropomorphize the weapons into masks redolent, with Cubist implications, of Picasso and Braque.

“When I compose my works, I try to create beauty out of the burdened material and make people reflect,” he explains. “My intention has been to transform something that was created for evil into something else, something better.”

Pascale Monnin, Haiti

ON JAN. 12, 2010, a magnitude 7 earthquake struck near the capital city of Port-au-Prince, the most populated place in Haiti. In 35 seconds, the lives of 3 million people—one-third of the population in the poorest country in the hemisphere—were abruptly changed.

An estimated 300,000 people died; hundreds of thousands more were injured; 1.5 million were displaced, rendered homeless, and sheltered in tent cities. Multistoried concrete buildings collapsed in deadly heaps because of poor construction; monuments such as the Port-au-Prince Cathedral and the National Palace—even the United Nations headquarters—sustained severe damage, as did the national penitentiary, permitting thousands of prisoners to walk away. An estimated 4,000 schools were destroyed, along with desperately needed health facilities. Then came the aftershocks. A 5.9 magnitude aftershock on Jan. 20 demolished many already weakened structures.

Two years after the earthquake, Hurricanes Isaac and Sandy flooded countless acres of crops, exacerbating the food crisis and thwarting recovery. In 2015 and 2016, 1 million people suffered through drought because of El Nino conditions. Then, in October 2016, category 5 Hurricane Matthew delivered a devastating punch to the country’s south, destroying Haitian artist Pascale Monnin’s house. It was a record-breaking and heart-wrenching pummeling by violent natural phenomena.

monninonlineedit.png

Monnin rechanneled all this cataclysm into inspiration. Her drawings of the earthquake results, almost unbearably tragic like Goya’s “Disasters of War,” were fundraisers for artist victims of the quake. With her husband, James Noel, she wrote and illustrated a children’s book about the quake, reliving “36 seconds longer than an eternity,” the howling dogs, the neighbor who went mad, the gray sky that Friday morning: “strange to see the cloud formations like the souls of the dead regrouped above our heads.”

That image resonates with “Memorial to the Disappeared,” the faces of children alive at the moment the earth trembled. It is composed of cement and iron, the building materials responsible for mass destruction, and left-behind shards of mirrors and glass. “I added broken mirrors,” she explains, “that reflect light, re-creating beauty, reshaping luminous, solar faces. How to create beauty out of what is broken ... how to wear scars as jewels that grow out of disaster.” They hang in the limbs of a so-called “Mimi blanc” tree, which loses all its leaves but blooms again every January, saluting—ever since its installation in 2015—the disappeared of January 2010.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!