IN 1948, A HERMIT was made known to the world by another hermit. Like many Christian holy men, the Jewish-born Catholic contemplative and poet Robert Lax had his early spirituality enshrined in a book: The Seven Storey Mountain, the bestselling autobiography authored by his friend, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton.

“He had a mind naturally disposed from the very cradle to a kind of affinity for Job and St. John of the Cross,” Merton wrote about Lax. “And I now know that he was born so much of a contemplative that he will probably never be able to find out how much.”

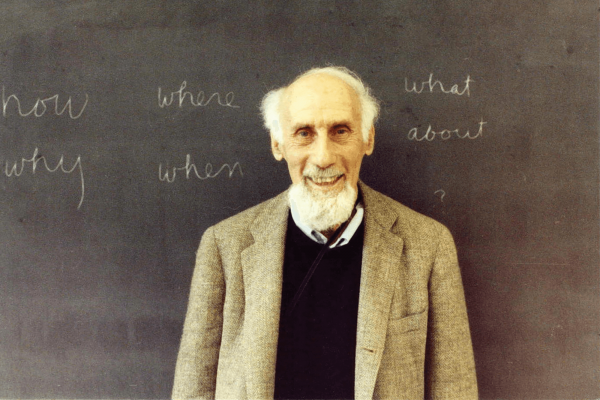

Better known to many for what was written about him than for what he wrote (and he wrote a lot), Lax, who died in 2000 at age 84, wanted, according to his archivist Paul Spaeth, “to put himself in a place where grace can flow.” For Lax in the 1940s, New York City was not such a place. Though he worked with the poor at Baroness Catherine de Hueck’s Friendship House in Harlem, and had enjoyed jazz with Merton, he balked at the gaspingly fast pace and materialism of the city. He was also unhappily employed at The New Yorker.

Read the Full Article