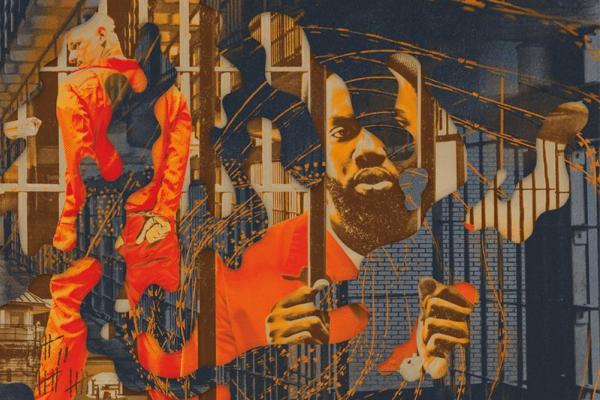

AMERICAN HYPERPOLICING and mass incarceration are products of 50 years of cynical politics, vicious economics, and unconscionable racism—as the mass uprising in the wake of George Floyd’s killing has brought into ever clearer focus. Across the country, organizers on the ground are pushing to defund the police. Meanwhile, for people Left, Right, and center, “ending mass incarceration” has become a standard political talking point. But what precisely would “ending mass incarceration” entail?

Imagine that tomorrow we were to enact the most radical reforms to the prison system conceivable—reforms tailored to mass incarceration’s political, economic, and racial dimensions. First, to scale down the war on drugs, we could pardon every person in state and federal custody who is incarcerated solely on the basis of a nonviolent drug offense. Second, to stop caging people simply because they are poor, we could release every pretrial defendant who is sitting in jail solely because they are unable to make bail. Third, to end what’s been called the New Jim Crow, imagine if every Black state and federal prisoner—who constitute one-third of those in prison—were freed, regardless of whether they were guilty of a crime. By committing to these three measures (which, needless to say, aren’t being seriously considered in Washington or in any state capital), the U.S. would reduce its prison population by more than 50 percent, to a tick over 1 million people. In the COVID-era especially, when prisons and jails are incubators of the virus, many lives would be saved. Families would be reunited. Much suffering would be forestalled.

What such a robust menu of reforms would not meaningfully do, however, is end mass incarceration. Even at half its current size, the U.S. incarceration rate would remain three times that of France, four times that of Germany, and similar degrees in excess of where it was for the first three-quarters of the 20th century. Given the massiveness of the American carceral edifice, we cannot reform our way out of mass incarceration. Nor does the reformist impulse address the crux of the problem.

The only way to end mass incarceration is with an abolitionist, not reformist, framework. Abolish prisons? But aren’t prisons necessary for public safety and for effecting justice? So, as a society, we have been conditioned to believe. But real public safety would begin with changing the social order that engenders poverty, illness, and desperation, not with the people—disproportionately poor, young, and Black or brown—whom this order criminalizes. As for justice, perhaps as a society we might collectively cultivate a vision where “justice” means something more robust and nourishing than merely putting the “bad people” in cages.

Does the public good require some small number of people to have their movements restricted for reasons of public well-being? For argument’s sake, let us concede that it may. Even if so, is our prison system the proper means to go about that? As with the death penalty and whatever the next war happens to be, for ordinary American citizens in the age of mass incarceration, the best move available politically is to stand up—together—and to categorically declare “no.”

Whether, like us, you regard locking a person in a cage as a moral abomination categorically, or whether you regard imprisonment as perhaps socially necessary but recognize the racism and classism that haunt our systems of imprisonment from top to bottom, by collectively assuming an abolitionist stance against human caging, we open up space for moral imagination and practical experimentation, and we gain leverage for securing marginal political victories.

The power of radical imagination

We write these words as scholars and practitioners of American religions who have worked with incarcerated people for more than two decades. As scholars, we have studied the power of the religious imagination to challenge the ways of the world, to loosen the hold of the purportedly immutable, and to motivate the pursuit of things deemed impossible. As religion practitioners and participants in social movements, we have experienced how religious tenets, practices, and narratives shape conceptions of justice and the people determined to effect that justice on the world. As friends of incarcerated people, we have seen how prisons are places where, in aggregate, people who have themselves experienced great harms are relegated for further suffering.

At the nexus of these subject positions, we would like to posit the following earnest provocation: Prison systems are a moral abomination and should be erased from the face of the earth. As a failed experiment and an engine of harm, the prison should be relegated to the scrapheap of bygone human endeavors. We can and must do better.

Easier said than done, of course. The network of institutions, supply chains, and social relations that abolitionists call “the prison industrial complex” is thoroughly embedded in our culture and is buttressed by a host of powerful material and political interests. If we are truly to end mass incarceration, these interests must be defeated. For this to happen, the social movement that began with the killing of Michael Brown and has intensified with the killing of George Floyd must continue to grow in size and power. As a mere conceptual matter, however, the principal obstacle for prison abolition rests on one thing and one thing only: its seeming impossibility. This is one “triumph” of mass incarceration, which, even in its manifest failure at ensuring public safety or engendering accountability, has succeeded at making prison a putatively essential American institution.

But here the abolitionists of old have everything to teach us. Two hundred years ago, it was a fact of life that some people were owned by other people. On the strength of the greatest mass movement in American history, a radical principle was inscribed by men and women into the purported nature of things: Slavery is a moral abomination. Not merely chattel slavery as it then existed in the United States, but slavery as such. The domination inherent in one human owning another human is not under any condition to be tolerated. This simple and uncontestable moral fact is a monumental historical achievement, and absent the courage and genius of generations of clear-seeing and brave people pulling together in the same direction, nature would to this day remain mute on the subject.

With the 2010 publication of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow , and intensified with the release of Ava DuVernay’s 2016 film 13th, it has become a fugitive species of American common sense that slavery, segregation, and mass incarceration constitute a painfully unbroken chain. This powerful movement narrative ought not to be understood simply as genealogical, however. It must also be understood as analogical. Is locking a human being in a cage a moral abomination on a par with a human being owning another human being? That people are caged by the state rather than by individuals, and that they are caged—nominally—for things they have done should not distract from the basic proposition. Human ownership and human caging each merit abolition because the domination inherent in each represents a fundamental abnegation of human worth.

Do our words ring in your ear as being somewhat “preachy?” That isn’t by accident. Making the impossible possible calls for an exercise in radical imagination, and it is precisely in this respect that religious ardor, or something closely related to it, becomes an invaluable asset. Without religious dreams, we will not even be able to envision what a truer, more just justice will look like.

In the same way that America has a prison culture, America also has an abolition culture. Just as American prison culture is imbued with religion, American abolition culture is also imbued with religion. Abolitionism’s revivalist spirit catalyzes social movements. It speaks the languages of divine coercion and absolute principle, and by doing so it challenges and reshapes the taken-for-granted ways of the world. It addresses concrete injustices, but its vision exceeds (and, when called for, even scorns) the pragmatic.

In the end, this revivalist spirit has the capacity to drive institutions for social democracy into existence. Today’s prison abolitionists are already moved by this spirit, but without getting religion—and igniting whole religious communities with abolitionist fire—prison abolitionism will never acquire its necessary force. Only a mass abolition-steeped fury will be able to tumble the walls down. Correlatively, we believe that only by embracing and avowing the abolition spirit will American religious communities live up to the moral demands of the present historical moment.

Experiments in the “impossible”

Across the country, in what abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba sometimes dubs “experiments,” community organizers are testing prototypes that could prefigure an abolitionist future. Under the rubric of decarceration, abolitionists push for legal and administrative reforms—“non-reformist reforms”—that shrink the footprint of the prison industrial complex. Under the banner of transformative justice, abolitionists work to remediate harms and engender accountability by nonviolent means. And in the form of mutual aid, abolitionists provide care and support, and bail people out of jail.

By talking to abolitionist organizers around the country, we found that these abolitionist experiments often are colored by religious and spiritual convictions. At the intersection of prison abolition and Qur’anic principles of justice and charity, a coalition of Muslim organizers in Chicago in 2018 launched #believersbailout, a campaign that during the course of Ramadan raised more than $100,000 that they used to bail people out of jail. The endgame is a world without prisons. “In the meantime,” as activist scholar Su’ad Abdul Khabeer put it, “like Abu Bakr freeing Bilal, like our enslaved African ancestors freeing each other, we’re going to free ourselves.”

At Chicago’s Second Unitarian Church, meanwhile, formerly incarcerated minister Jason Lydon decries in bold theological terms the evil of the prison industrial complex, blaming in part a “violent Calvinist theology” that pervades American common sense. Politicians and prison administrators frame prison as addressing violence, brutality, and abuse, but in Lydon’s view prisons merely reroute these pervasive American problems onto the bodies of specially designated victims (people living in poverty, Black people, and queer and trans people disproportionately): “We have public trials of individuals who have done something terrible, and these people take on the sins of all those who have inflicted harm. In watching these scapegoats be tried, convicted, incarcerated, and experience the many harms and violence of incarceration, survivors of violence are supposed to receive some kind of healing. This, we are told, is ‘justice.’”

But for Lydon, humans are sacred and human life is to be valued without exception. To give God and human beings what they are properly due means fighting to eradicate institutions that damage and replacing them with practices that restore. Toward this end, Lydon founded Black and Pink, a group organizing with and on behalf of incarcerated LGBTQ and HIV+ prisoners.

Pastor Lynice Pinkard, who was ordained in the United Church of Christ, describes how under capitalism and Constantinian Christianity we came to mistakenly believe that the liberation of our own subgroup depends on the domination of others. For Pinkard, there is no sacrificing the “wicked” in service of the righteous. For any of us to be saved, all of us must be saved together. In 2008, Pinkard was a founding member of Seminary of the Street in Oakland, Calif. Among its activities, Seminary of the Street executes “liturgical direct actions,” such as when it bloodied the Alameda County Courthouse steps with red paint on Good Friday to call attention to the imperial violence of the criminal justice system.

Like Lydon, Pinkard, now in North Carolina, counsels us to resist the cheap, bloody catharsis that the criminal justice system cynically dubs “healing.” Rather than find false consolation in the suffering of “the guilty,” Pinkard encourages us to sit with our despair. There we can begin the arduous labor of bringing “love and tenderness to ungrieved losses, relational estrangement, [and] internalized oppression.” In time, Pinkard says, “We begin to form coalitions to make structural changes—meaningful work that pays a living wage, community safety patrols to replace police presence, restorative justice processes.” This is a spirit of abolition that inheres in everyday practices of survival and healing, repair and resistance.

In Philadelphia, we spoke with Kempis “Ghani” Songster, who was sentenced to life without parole at the age of 15. In 2016, the Supreme Court held that juveniles sentenced to life without the possibility of parole must be eligible for release, and Songster knew that his hour of freedom might soon be at hand. Songster saw a problem. Violent crime is largely horizontal, with harmers and the harmed coming from the same communities, but the state’s adversarial system pits community members against each other in a zero-sum game.

“Part of political action,” according to Songster, must be “healing action.” Too often, he laments, this aspect of abolition has been ignored. Songster looked to Africa for models of post-conflict justice, to the Truth and Reconciliation process in South Africa and community-based Gacaca courts in Rwanda. In 2016, while still incarcerated, Songster co-organized an event that brought together newly paroled former juvenile lifers and the families of those victimized by violent crime. Drawing on the Gacaca model, men who had killed were afforded the opportunity to admit what they did, to apologize for what they did, to seek forgiveness, and to explore possibilities of atonement. They were invited to pledge to become agents of change in their community. No longer incarcerated, Songster continues his work with Ubuntu Philadelphia as well as with the Abolitionist Law Center and the Amistad Law Project.

A stubborn pursuit

Abolitionist dreams begin where impossibility leaves off. As agents of the most transformative social movement in our country’s history, the 19th-century abolitionists are also an enduring, if malleable, archetype. As Andrew Delbanco ambivalently characterized them in his 2012 book The Abolitionist Imagination, abolitionists represent “a recurrent American phenomenon: a determined minority sets out, in the face of long odds, to rid the world of what it regards as a patent and entrenched evil.” As incarcerated journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal puts it, “Abolitionists are, simply put, those beings who look out upon their time and say, ‘No.’”

The will to abolish is what comes forth when pessimism about the possibility for effecting justice hits rock bottom and careens back up in the form of righteous fury.

Whereas reform begins with the essentially secular stuff of data and policy, abolitionism plumbs a deeper, more soulful well. Whereas the call to “end mass incarceration” is merely quantitative, the call to abolish prisons is qualitative. This shift is mobilizing, righteous, and corrective: The problem isn’t merely that there are too many people confined to American cages; the problem is the cage itself. As a moral abomination, even one caged person—adult or child, white or Black, documented or undocumented, “innocent” or “guilty”—would be too many.

If prison reform requires new policy proposals, prison abolition necessitates fundamental changes in the ways we understand justice and injustice, harm and accountability, entitlement and obligation. At its most progressive, reform aspires to improve conditions, rehabilitate offenders, reduce recidivism, and shrink prison populations—all the while conceding that “public safety,” a notion deeply entwined with the logic of mass incarceration, is a condition achieved through the proper administration of state violence. Abolitionism refuses these languages and instead insists on principles, on absolutes, and on truths, in stubborn pursuit of a world without prisons

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!