GROWING UP, I read tons of historical fiction and often imagined the lives and times of my ancestors. My curiosity stemmed, in no small part, from my family, who dragged us to every available Black history and Black art museum. Whether visiting California’s first and only Black town, where my great-great-grandparents had bought land; making a pilgrimage to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center during a family reunion; taking Black history bus tours; or hearing family stories from my grandmother and great-aunt, Black history was never far from our everyday lives.

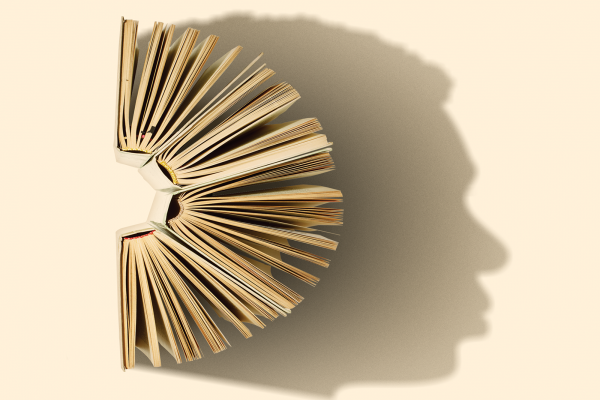

Recently, technological developments and my growing archival research skills have enabled me to dig further into our family history. As DNA ancestry testing and digitized documents have become more widespread, I have been able to find graves and documents that could have been lost to history. The past, for me, has become even more close at hand as a crucial way of understanding the present.

Relating to the past in this way—an approach that resonates with Black families across the diaspora—stands in stark contrast to ongoing efforts to erase, distort, and lie about history. State legislatures, boards of education, and church groups such as the Southern Baptist Convention have taken steps to ban the teaching of “critical race theory” (while showing little evidence that they understand what CRT even is); private Christian schools assign right-wing U.S. history textbooks describing chattel slavery as “immigration”; conservative politicians promote racist, whitewashed mythologies as American history.

Such heresies make me angry. However, while historical argument and political advocacy is needed to refute these lies, I find myself pondering the spiritual resources necessary to offer a more honest version of our past, present, and future. The deepest wells from which we need to draw are not just historical. The title for this column, “Under the Sun,” echoes a passage from Alice Walker, who says of Southern Black writers, “having been placed, as Camus says, ‘halfway between misery and the sun,’ they, too, know that ‘though all is not well under the sun, history is not everything.’” The most profound testimony against historical heresy is found in the fabric of people’s lives.

I think about people like Dan Smith, an 89-year-old man who is the son of Abram Smith, a former slave. When you realize that there are still people alive who are the children of former slaves, slavery doesn’t seem that far away. I think about Simeon and Anna, elders who waited on God’s promise and then witnessed Jesus’ presentation in the temple, showing Advent to be as much about the past as about the future. I think about elders like my 106-year-old former neighbor, now deceased, who was born when women (and many Black men) couldn’t vote and who lived to vote for the nation’s first Black president. And my great-aunt, still living, who helped me regain historical perspective on Nov. 9, 2016, by chuckling and saying, “You think this is bad?! Oh, honey, you ain’t seen nothing.”

Simeon and Anna; the reality of one generation removed; the witness of ancestors still living and passed on—these offer their own testimony against futile efforts to deny the past. They remind us that salvation is needed, and comes, to this history, this past that is still present.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!