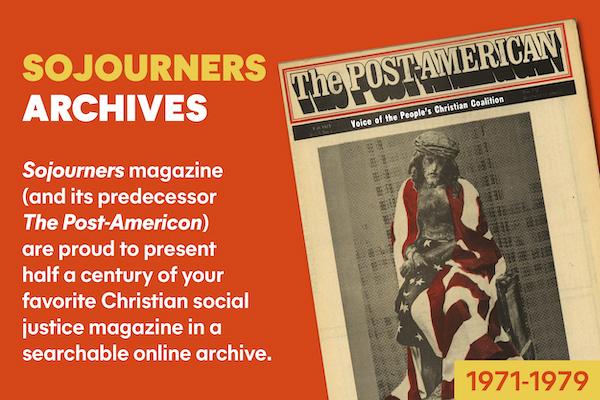

Thesis One: "The Christian faith has revolutionary implications for human life and society."

From an examination of the teachings of the Bible, it is evident that the apostles and prophets held the belief that true religion would necessarily revolutionize the conditions of life into which it came. Amos spoke, the word of God:

Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen. But let justice roll like waters, and righteousness like an everlasting stream (Amos 5:23-24).

Jeremiah insisted that social justice ought to be visible in evidence of true faith (22:3):

These are the words of the Lord: Deal justly, rescue the victim from the oppressor, do not ill-treat nor do violence to the alien, the orphan or the widow, do not shed innocent blood in this place.

John the Baptist made plain the demanding ethical implication of his message. Jesus himself consistently stood with the poor and dispossessed. He upheld the dignity of women against his culture. His parable of the Good Samaritan clearly states our responsibility to all that are needy. The apostle Paul insisted that Christ has dissolved the old segregations between bond and free, and Jew and Greek. James bluntly said that faith that did not issue in practical concern for people's needs was phony and useless. The Christian faith calls into question all the structures of this fallen order, and places them beneath the judgment of an absolute ethical standard.

Thesis Two: "Institutional Christianity in

Read the Full Article