So far President Reagan's "zero option" proposal on medium-range nuclear missiles in Europe has successfully defused the issue on this side of the Atlantic. It has been hailed as a bold initiative for peace, one seemingly out of character with Reagan's earlier foreign policy posture. But in retrospect it will probably look more like a bold media coup consistent with the president's uncanny knack for selling, via television, the most disastrous policies.

This will likely be the case because it takes two to negotiate, and the Soviets see the zero option as a completely one-sided proposal for them to give up something for nothing. They simply don't consider their SS-20 missiles to be equivalent to NATO's proposed Pershing 2 and cruise missiles.

That Reagan agreed to begin the Geneva talks at all was solely due to political pressure from Europe. That, added to the fact that the chief negotiator for the U.S., Paul Nitze, is the man who created much of the present Cold War hysteria through his Committee on the Present Danger, makes it likely that the zero option will prove to be more a ploy to buy time in hopes that the European Peace Movement falters than a serious negotiating position.

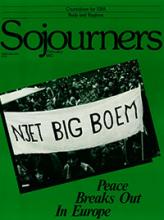

In his internationally televised speech in November, Reagan laid out the rationale for the deployment of Pershing 2 and cruise missiles in Europe in a format that gave no opportunity for questions. And to this day some very basic questions about the necessity and wisdom of the missiles program still haven't been raised sufficiently in this country. They are questions that the European Peace Movement has been raising and answering for almost three years now. But the Europeans' arguments have received little attention in this country, where moderates see the movement based on alienated youth's irrational fear of the future and conservatives see it based in Moscow.

Read the Full Article