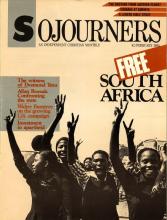

In a bold and calculated move, South African bishop and Nobel laureate Desmond Tutu last month called on foreign corporations investing and operating in his country to push for specific reforms in South Africa's apartheid system.

Speaking at a press conference in Johannesburg just a few days after his return to South Africa, Tutu said a campaign of "persuasive pressure" is the nation's "last chance to avert a bloodbath."

Tutu also threatened economic sanctions against the foreign corporations if they do not succeed in forcing substantial changes in apartheid policies within a test period of 18 months to two years. The archbishop insisted that his proposal was not overly high-handed or demanding, but was intended to "show that we are trying to be reasonable. We are saying, 'Please can you give us a way of changing apartheid reasonably peacefully.'"

Upon his return to South Africa, Tutu apparently was confronted with internal tensions volatile enough to compel him to commit the breach of South African law there that he would not violate when speaking in the United States. When Sojourners had asked him just two weeks earlier at a Washington press conference if he supported sanctions against U.S. companies in South Africa, Tutu replied that it would be against South African law to do so. Media representatives would just have to use their "common sense and good judgment" to determine his feelings on the matter, he said.

But at the same press conference, Tutu expressed grave concern about the volatile situation in his country, saying that while he hoped there would be no widespread violence, he supposed the situation could "explode at any time."

Read the Full Article