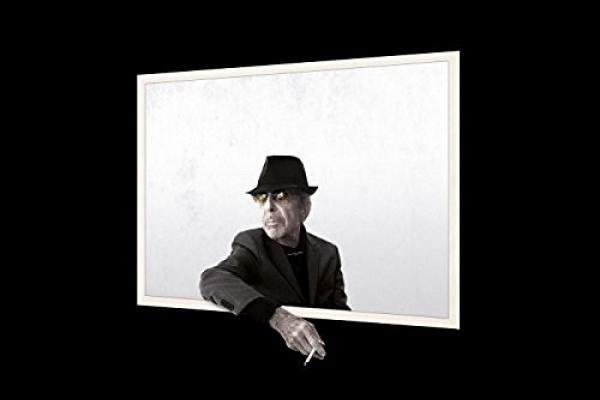

A PERSON HAS a thousand ways of being, not just one but many selves, and Leonard Cohen embraced them all.

He sang the blues with Old World struggle, rasped epic tales and sometimes gospel, strumming Spanish chords on a broken-down guitar. But his final album, You Want It Darker, released a month after his 82nd birthday and only 17 days before he passed away, was like someone transcendently singing the prayer for ascension at his own funeral.

As if chanting a private liturgy, there was no more hunger for a voice. At last Cohen was the praise singer, aged and fatigued, a pilgrim with just one journey left to make. From the opening supplication—“I’m ready, my lord”—to the closing blessing—“It’s over now, the water and the wine”—the album is an uninterrupted prayer unto death.

“Traveling Light,” You Want It Darker’s ecstatic peak, bids au revoir to the self and the soul, the lover and beloved, the human and divine. Even in old age, Cohen is still no preacher, sage, or a saint. “I’m just a fool / A dreamer who / Forgot to dream / Of the me and you / I’m not alone / I’ve met a few / Traveling light / Like we used to do.”

Gone is the seductive blurring of sacred and profane and peeking through the curtain to glimpse the dealer’s latest game. The verses slide into an older and saltier way of singing, a sacred undertow, always there in songs of love and of despair, now amplified by the kind of wordless prayer people once sang from dusk until dawn.

In an era of singer-songwriters, Leonard Cohen was often heralded for his verse. But he was a master of melody, especially when he dropped into the special sadness of this ancient mode, whose every note is a variant of the Song of Songs.

To his end of days, he said music was an unsolved puzzle, insisting he was guided by neither angels nor a muse. “If I knew where the good songs came from,” he quipped, over and again, “I would go there more often.”

More often?

Just let the canon play on an endless loop, and even the serious acolyte will soon be asking, “What is this marvelous song I have never heard before?”

“Reject the angel, and give the muse a kick,” said Cohen’s beloved Federico Garcia Lorca, the Spanish poet and playwright. “The true struggle is with the duende.”

The angel guides and the muse dictates, Lorca explained, but duende—the creative spirit of earth that everyone feels but no philosopher has explained—appears only when the seeker is conscious that he might suddenly be devoured by ants. With death in the foreground, the seeker is worthy of his suffering and sincerity, sincerity being the key that unlocks sacred music.

Perhaps the music was as Cohen said, all toil, sweat, and mystery, like a metalworker alloying songs in silent factories. But in a world where sacred song no longer springs naturally from daily life, his creative imagination was as miraculous as it was prodigious.

At the end of You Want It Darker, a string quartet reprises the melody of “Anthem,” whose signature verse “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in” has rescued countless preachers furiously cribbing their sermons. It is just the melody now, graceful and serene, until we hear a voice chanting, one exalted final line. “I wish there was a treaty, I wish there was a treaty, between your love and mine.”

One wants to rise, applaud, cry out, “A thousand kisses, dear Leonard! You gave us exactly what we want!” Yet more than any verse or melody, it is something in the album’s liner notes—a simple paragraph of gratitude, from a father to a son—that blows the place away.

When Cohen was unable to complete the album, his son stepped in and salvaged the project. I don’t know a thing about their relations, except to say: For any father and son to be at peace, let alone enrich the world with sacred music, is not just redemptive, it is messianic. It’s written in the scriptures; it’s not an idle claim! “Before the coming of the great and awesome day” arrives the sage Elijah, the prophet Malachi explains, ending a war more divisive and insane than conflicts between nations—hatred between parents and children.

Even in a time when, as Cohen wrote in “The Future,” the “blizzard of the world has crossed the threshold, and it has overturned the order of the soul,” it is still easier for most of us to imagine geopolitical than familial peace. But what he called bringing “gratitude back to the soil” was Cohen’s highest discipline, and his life, his work, and legacies are whispered messages that beauty and dignity remain the province of humanity.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!