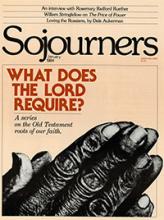

He has showed you ... what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?

(Micah 6:8)

Many of those in the churches who are most concerned for the witness of the Christian faith in the social order find themselves hard pressed to describe a significant role for the Bible in that task of social witness. It is not that they do not honor the Scripture, but that it seems to become a kind of distant historical background rather than a direct resource in addressing the urgent needs of our broken world. A very committed pastor once said to me after I had spoken on biblical understandings of hunger issues, "That was interesting, but we really don't have time to be reading the Bible. People are starving out there."

One of the reasons for this is that Christian social witness in our time has become chiefly identified with the "doing" side of the Christian moral life. "What shall we do about X?" You can fill in any issue of concern: peace, racism, poverty. The emphasis is on decision making, strategy, and action. Some of the church's finest moments in our time have come when Christians made decisions of conscience and courageously acted on those decisions.

Read the Full Article