WHEN DUTCH ARTIST Sarah van Sonsbeeck sees photos of people wrapped in metallic emergency blankets and referred to as “migrants” or “refugees,” she’s disturbed by the way this reduces their humanity. “This abstraction, I feel, is very dangerous,” she says.

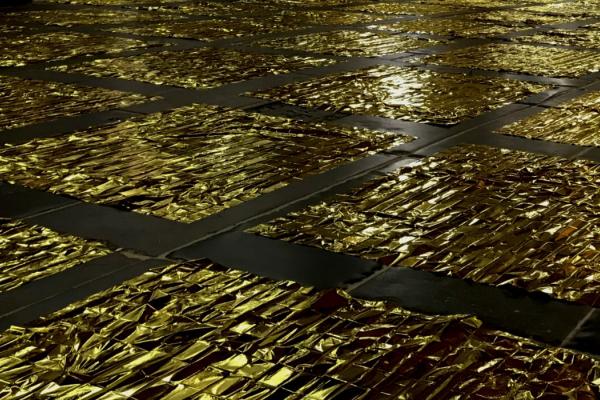

Van Sonsbeeck brought hundreds of gold-and-silver Mylar blankets to Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk (“Old Church”) for a site-specific installation last May to September. The exhibit reflected upon the church’s colonialist history and the ways that Westerners can be unwittingly complicit in migration. The last point troubled the artist from the start of her project.

“As I am not a migrant, am I even entitled to address this?” she asked herself, before realizing she too plays a role. “I belong to and am a product of the Western society the migrants are migrating to,” she says.

Just as Mylar blankets can obscure people’s humanity, van Sonsbeeck’s installation, which evoked ripples in a golden sea when the light hit off the Mylar, covered many of the 2,500 tombstones marking some 10,000 graves that make up the church floor. Some of Amsterdam’s most prominent business people, politicians, and military leaders are buried beneath the 13th century church, and Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, is another renowned long-term resident.

Read the Full Article