I GREW UP IN Guatemala, a country where the Indigenous people make up more than 50 percent of the population. I was told growing up that my ancestors were Europeans (Spaniards and Italians). Even though I was identified as ladino (not Indigenous) by Guatemalan official nomenclature, I was attracted to Mayan languages and communities (K’iche’, Kaqchikel, and Q’eqchi’, among others).

I felt a resonance with their orientation toward the earth, their deep sense of communal cohesion, and their mystical world of ancestral spirits. After doing some genealogical work, I learned that one of my grandfathers was Mayan.

I began to notice practices and attitudes in my family that I was certain were of Indigenous origins: my dad’s idiosyncratic disregard for manufactured material goods in favor of plants; my uncle’s pouring of alcohol on the floor before serving a drink; my mom’s smoking of cigars as an invitation to the spirits and San Simón to be with us in our gatherings. All have an Indigenous provenance.

As I learned more, I recognized those familial practices as part of a millennia-old cosmovision and mindset, a way of viewing the cosmic order of a civilization through which Indigenous peoples organize everyday activities, even today. Each is a theo-ethical gesture for safeguarding their relationship with life itself, in all life’s diversity.

My travels around other Latin American nations have allowed me to interact with other Indigenous peoples and learn from their traditions and wisdom. As a scholar, I have also encountered similar patterns of life among First Nations in Canada and Native Americans in the United States.

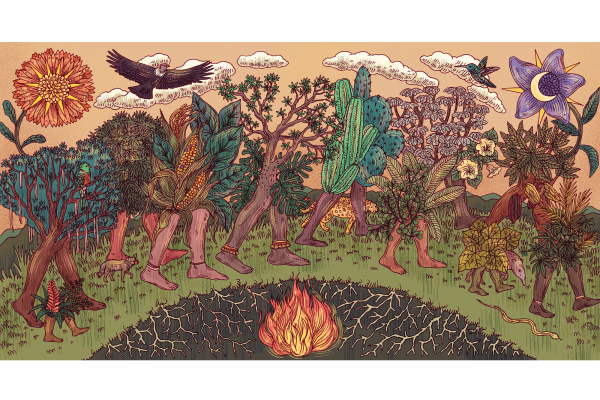

Through the large expanse of the Americas, these ethnic groups and communities share common views of the origins of the world. They share an understanding of the earth as teeming with life; all of them operate within a mystical-spiritual relationship that weaves together the earth, the spirits of their ancestors, celestial bodies, other forms of life, and humans.

In these cosmovisions, humans are not the most important agents, but are also not neutral bystanders. For example, Berta Cáceres’ activism for the protection of Honduran ecosystems against transnational mining corporations was not only the work of an “environmentalist.” Her work was deeply rooted in an Indigenous cosmovision that gives priority to protecting the sustaining life force of the earth and understands humans as key agents in that effort.

Buen vivir

These approaches to life remind me of what Indigenous peoples in South America have dubbed buen vivir (literally, good living). Buen vivir emphasizes a holistic approach to life that requires rethinking the social structures and dynamics that shape people in community and how those structures directly impact the environment. Buen vivir refers to a qualitative measure of the relationships between people, others in their community, and their surrounding environment. It envisions a different way to build society.

Those communities that subscribe to buen vivir are built on the principle of profound interrelationship—individuals are linked to a larger diverse communal whole, which includes nature and the spirits of the ancestors and animals. Ideas like “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” for example, are understood in a collective sense, not in terms of individual rights and privileges. Individualist focus disrupts the communal equilibrium based on coexistence and the survival of the community. The consumption of natural resources and concepts such as “absolute” ownership of property are measured in relation to the survival of the members of the community and how those concepts protect existing natural resources for generations to come.

At its heart, buen vivir presupposes the collective ethical imperative to protect life in all its forms. Unlimited extraction and exploitation of natural resources, individual accumulation of wealth, and forced cultural assimilation are fundamentally antithetical to buen vivir. What these communities seek to build are “plurivocal” societies where many voices are heard, and the central axis of existence is not humanity but the larger structures and forces that sustain life on the planet. In buen vivir, the values of interrelationship and interdependence, the survival of each other, and the preservation of natural ecosystems are all preconditions for the survival of the community.

Buen vivir provides a framework for understanding life, people, community, and the divine from the vantage point of mutual coexistence. In the mythical cosmovisions of Indigenous peoples, humans are understood to be part of the larger vortex of life that connects all living things. Respect for life in its richly diverse expressions requires unique interactions with each living thing. Diverse peoples are celebrated as heirs to diverse forms of knowledges and life experiences. They are not catalogued according to prejudiced ethnoracial differences. Nature is not seen as a material repository of potential products for consumption. Instead, the earth is properly appreciated as the “mother,” the life source that sustains all. If something happens to nature, the entire structure of life falls out of balance and the future of life itself is at risk.

Across the continent

Buen vivir is not unique to the Indigenous communities of South America. I’ve also encountered it among the Zapatistas, as they continue to reclaim self-government in Chiapas, Mexico. Two main features of the Zapatista social structure are an affirmation of the bonds of mutuality and a refusal to adopt punitive approaches to policing and fighting crime. To safeguard the community, they’ve chosen a model of “transformative justice,” an approach that focuses on the restorative nature of justice, not punishment. In Guatemala, the Mayan phrase “Utz’ K’aslimaal” (good life or a life in balance) is another example. The concept conveys a similar proposal as buen vivir.

Cognate terms from other ethnic groups in Latin America describe similar realities. Orlando Fals Borda and Arturo Escobar remind us that among Afro-Colombians from the North Cauca river communities, the governing idea is sentipensar (literally translated as to think-feel). Sentipensar focuses on communities’ attitudes in carrying out their daily activities—as they consider the effect of each choice and action on the water and the fish in the river from which they draw their sustenance and on the land that feeds them.

The first Encuentro del Buen Vivir held in Mexico in 2012 and the seventh Encuentro Internacional por el Buen Vivir held in Peru in 2020 are examples of the wide range of Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities that resonate with the principles of buen vivir across the continent.

Some refer to buen vivir as if it were a recent development. But women’s rights activist and Guatemalan Indigenous leader Aura Lolita Chávez Ixcaquic reminds us that these cosmovisions are part of the long-standing legacy of generations of Indigenous ancestors who have lived this way. The crucial teaching of buen vivir is that the Indigenous communities of the Americas are offering us a proyecto de vida—a “life project”—that runs on a different path from the pervasive structures of capitalism, commodification of life, and extraction of natural resources.

Buen vivir is informed by a logic that views the multifaceted and multiform expressions of life as sacred, therefore it resists reducing life to the lowest common denominator of capital. The value of human labor is in its responsibility to actively strive to preserve the fragile balance between humans, other forms of life, the earth, and the ancestral spirits—not in amassing wealth or producing material goods.

A project of death

Among Latin Americans, when an individual has great financial resources, they are said to vivir bien (to live well). But such a mode of living focuses on ideas of individual abundance and affluence with little consideration of the impact such wealth has on the environment and the community. The Indigenous concept of buen vivir highlights the importance of consuming only what one needs. The goal is not unfettered economic growth but sustenance for all. In other words, it goes beyond the horizon of normative economics through capital. The more I think about these dynamics, the more I am convinced that buen vivir stands on a different path than the pervasive structures of the Doctrine of Discovery—and the colonization and capitalism that accompany it.

The Doctrine of Discovery—a series of edicts that established a theological, political, and legal justification for European colonization and seizure of lands that were not inhabited by Christians—developed over time. By the middle of the 15th century, such edicts had become a legal mechanism that the Portuguese, who sought to invade the Canary Islands and North Africa around 1436, used to justify enslaving Africans. The Portuguese colonizers received “full and free permission” from Pope Nicholas V through the papal bull Dum Diversas (1452) to “invade, capture, and subjugate” the non-Christian inhabitants. Shaped by notions of European ethnoracial, civilizational, cultural, and religious superiority, the doctrine became the catalyst for the Western European military, genocidal, and colonizing project, through which Western Europeans (and eventually Americans) invaded and took possession of Indigenous lands around the world.

From a Western European perspective, the logic seemed flawless.

But from the perspective of what theologian Enrique Dussel calls “the underside of modernity,” the Doctrine of Discovery paved the way for globalized market capitalism in its multiple expressions. Ideas of the commodification of bodies and of life itself—as well as the adoption of a racialized social evolutionary construction of societies—all stem from that doctrine.

The “imperial gaze,” which saw the earth as the repository of quantifiable wealth (in capitalist terms) and was pervasive in European conquests, has contributed to rapacious attitudes today that view natural resources as freely available to provide and serve the needs of humans. The extraction of natural resources—such as minerals, oil, and precious stones—is the extreme manifestation of the doctrine’s logic of the commodification of nature and epitomizes the radical qualitative separation between humanity and the rest of creation. This worldview runs counter to everything for which buen vivir stands. Capitalism enshrines the doctrine’s attitudes of despoliation of nature behind a facade of progress, advancement, and modernity.

A project of life

In 1615, Quechua Peruvian Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala wrote El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government) , which he sent as a handwritten manuscript to King Philip III of Spain. After 30 years of research across South America, Guaman Poma concluded that the Incan empire and society were all-around better than the colonial rule imposed by the Spaniards, who had arrived in the Incan region in the 1530s. He bolstered his conclusions by identifying the ways Indigenous peoples were maltreated, and he detailed the hypocrisy of Europeans who did not live up to the standards of their own proclaimed religion—one that valued love of neighbor, peace, hospitality, and deep reverence for their creator God.

I would posit that not much has changed since then. Indigenous origin stories and cosmovisions continue to articulate their peoples’ relationship with the existing world in similar ways—and continue to believe those understandings to be “better.” Be they Guaraní, Quechua, Aymara, or Maya, among others, their understanding of the world and society are diametrically different from those the Europeans brought to the Americas.

Through the notion of buen vivir, these Indigenous communities challenge all of us to reconsider our attitudes toward each other, ancestral spirits, other peoples, and the world. They offer a radically alternative “life project” that stands against oppressive European-rooted systems steeped in the heritage of colonialism and capitalism (including racialized discrimination, hyper individualism, and unfettered contamination of the environment).

It could be said that the Doctrine of Discovery is actually part of a “death project” that perpetuates the radical disconnect between human groups and between humans and other living things and the earth. This death project requires military activity, violence against the environment, and the exploitation of other human groups to subsidize the extravagance of the few. Many refer to this “end of the world” time as the Anthropocene—a geologic era not only of human modification of the natural world, but one in which humans have the power to eradicate human life altogether.

In contrast, buen vivir emphasizes the radical interconnectedness and interdependence between all living things, as well as between human groups. The end game is to work together and coexist to ensure the survival of the human community today and for seven generations to come. Attention to the logic of buen vivir enables the diagnosis of root causes for the impending doom, of which global warming is only a symptom.

As Lolita Chávez teaches, “We draw strength from many principles, including reciprocity (‘you are me and I am you’). That gives us strength as women and this connection with life and the network that we all form. ... So, as part of that mesh, we declare that we must have territories free of companies and free of violence against women, and that empowers us so that we can say that we are moving toward the full meaning of life.” That’s buen vivir.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!