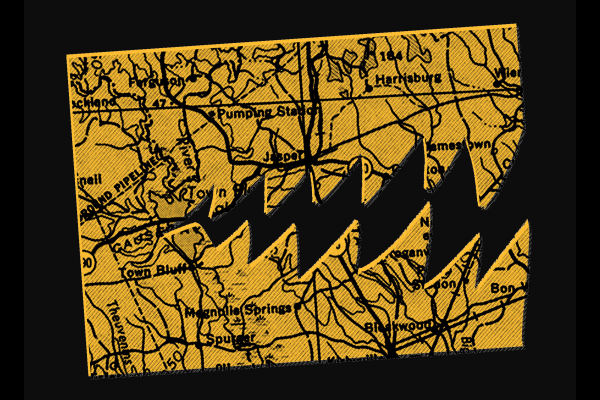

WHEN I WAS 8 years old, in June 1998, three white supremacists lynched James Byrd Jr., a Black man in Jasper, Texas. After offering him a ride in their truck, they beat him, desecrated him, chained him to their vehicle, dragged him to his dismemberment and eventual death, and deposited parts of his body in front of a Black church to be found on Sunday morning. I remember hearing about the murder on the evening news and having a newly personal sense of the geography of racial terror. As a child living in California, I could not locate Jasper on a map, but its name, and Byrd’s, were forever fixed in my mind.

Earlier this year, I realized that my great-grandmother was around that same age when, in May 1918, white supremacists lynched Mary Turner and a dozen other Black people, including the baby they cut out of Turner’s abdomen. I wonder if my great-grandmother, as a child, heard the news, and how it affected her. In her case, the lynchings happened not three states but three hours from where she lived in Georgia. Unlike in Byrd’s case, there were no charges, arrests, trials, or convictions of the known and suspected murderers behind these lynchings. I wonder if and how the killings—and the impunity allowing the lynchers freedom of movement—shaped her sense of the landscape.

In Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, geographer Katherine McKittrick writes that “Black matters are spatial matters.” McKittrick identifies the social production of space—how landscape is not a fixed background but is defined by relationships. Fugitivity, precarity, and possibilities of life and death are mapped realities that follow social relationships.

Read the Full Article