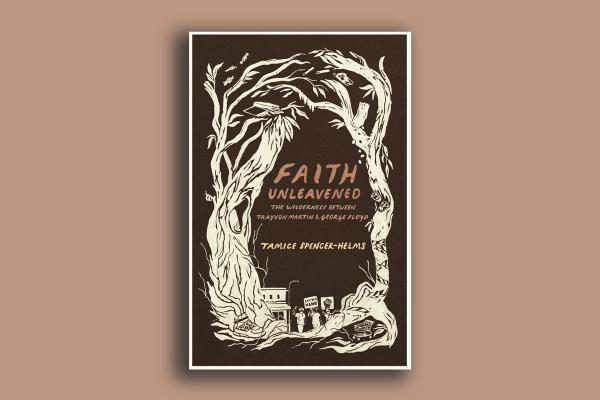

I DON'T KNOW if theologian Tamice Spencer-Helms can pinpoint the moment she met Jesus — she was raised in a Black church. But she remembers vividly where she met “white Jesus.” As she relates in her new memoir, Faith Unleavened: The Wilderness Between Trayvon Martin and George Floyd, Spencer-Helms met white Jesus when she was a teenager, and she met him in hell.

This hell was the set of a “judgment house” in a white evangelical church Spencer-Helms was attending at the invitation of a friend. Judgment houses are reimaginings of haunted houses, where visitors are presented with horrifying scenes of people who did not convert to Christianity and ended up in hell. At the end of the experience, “Jesus,” who, spoiler alert, is the pastor of the church, appeared garbed in white, descending a golden staircase. Spencer-Helms recalls, “This Jesus was different than the one in the pictures on the walls in my home — he was tall with straight brown hair and had thick eyebrows above his blue eyes.”

So began the theological colonization of Spencer-Helms, one that taught her to hate her Blackness and despise Black theology.

Faith Unleavened begins with Spencer-Helms’ memory of the murder of Trayvon Martin. In Martin, she saw the figure of her brother. But when she approached her faith community, she found no solace: “At church, the day after the jury acquitted Trayvon’s killer, they talked about how sad it was that the guy from Glee died.”

Her church’s inability to bear witness to her grief and fear — and by extension, their inability to bear witness to the war being waged on Black bodies — drove her to what many are calling “deconstruction.” But for Spencer-Helms, a queer Black woman, this is more than deconstruction — it’s decolonization. She finds a parallel between her experiences and those of the ancient Israelites in their journey of liberation from Egypt: After fleeing an oppressive theology, she is wandering in the wilderness, not yet home in a new faith.

Spencer-Helms draws the title of her book from the unleavened bread served as part of the Exodus from Egypt. “Bread without leaven contains only essential items,” she writes. “It has no additives, no preservatives, no added sweeteners. It is just flour and water — flat and unpretentious. Bread with leaven, like that of the Egyptians, became bloated as it rose and took longer to digest.”

Spencer-Helms investigates the “leaven” of white supremacy — how it was introduced to the “dough” of faith — and what it means to leave it behind.

In this endeavor, Spencer-Helms is largely successful, weaving memoir with biblical stories, church history, and contemporary racialized realities. But not every component is as fully realized as the others. Her “White Jesus: An Origin Story,” for instance, is technically accurate but incomplete, ending not long after the Council of Nicaea. She glosses over more than 1,000 years of church history, including how European Christians crafted the category of race.

Spencer-Helms focuses primarily on the white Jesus’ hellish influence on Christianity and society. She illustrates how malnourished her faith had become at white Jesus’ table. And she gives us glimpses of the Promised Land — a faith in the footsteps not of the colonizing white Jesus but of the brown-skinned Palestinian liberator.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!