IN HIS BOOK The Islamophobia Industry, author Nathan Lean points out that two months after the attacks of 9/11, Pew research showed that 59 percent of Americans had a favorable view of Islam. That was a 14-point increase from a similar poll taken in March 2001, several months before the Twin Towers fell. This was likely because U.S. leaders, including President George W. Bush, stated publicly and repeatedly that Islam and Muslims were not to blame for terrorism—terrorists were.

By October 2010, nine years later, only 39 percent of Americans expressed a favorable view of Islam.

What accounted for this dramatic drop? Yes, Muslims committed 11 terrorist attacks on U.S. soil during that period, attacks that tragically took the lives of 33 people, but this hardly seems overwhelming in a nation that experienced 150,000 murders in the same time span. Lean concludes that the “spasm of Islamophobia that rattled through the American public is the product of a tight-knit and interconnected confederation of right-wing fear merchants ... the Islamophobia industry.”

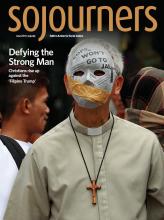

The controversy the “industry” generated around Cordoba House (the original name for what became known as “the Ground Zero Mosque”) was its first taste of sustained mainstream public influence, but it would not be the last. A few years later, many denizens of this world were either in or orbiting the Trump campaign and later his White House. “Fringe, Sinister View of Islam Now Steers the White House” was how a New York Times headline described it.

Trump himself appears to embrace this worldview. During the presidential campaign, he repeatedly made comments such as “I think Islam hates us” and threatened to enact this worldview into policy.

Read the Full Article