“IN THE BEGINNING was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” I had no idea what the words I recited in front of the church meant. My Mary Janes hurt my feet and my dress was so tight it left angry red welts in my armpits. Mom looked so proud; Dad, too, sitting in the front row, smiling. I didn’t want to disappoint them, especially here.

As far back as I can remember, my parents started churches in our suburban Milwaukee home. They were nondenominational, Independent, Calvinist, Fundamentalist Baptist. Initially, just a few families gathered, with Dad leading the service in our living room. Before long, our house overflowed, and the adults started raising money to construct a church. Once the building was complete, dissension began and my parents would leave, claiming the church was now too liberal. They disapproved of so many things: changes to the prayer book, Black people joining their all-white communities, homosexuality, women in ministry, the Equal Rights Amendment, anyone who questioned the literal translation of the Bible, adding rhythm to traditional hymns, accepting Catholics as fellow Christians. We were the “Chosen.” Predestined and proud of it.

My parents were also active members of The John Birch Society (JBS), the extreme right political organization, founded in 1958, which is known to be racist and antisemitic. They hosted monthly JBS chapter meetings in our living room. It was hard to know which belief system drove them more: the conservative politics of the JBS or the fundamentalist Christian fear of the rise of the Antichrist. Either way, to them the possibility of a communist invasion was a real threat.

They hired a handyman to build a hidey-hole in the back of the closet in our basement, where our whole family could hunker down if communists invaded the United States. Because we were Christians, educated, and part of the ruling class, Mom told us our family would be among the first to be imprisoned, then executed. Most of my nightmares as a child involved communists finding us in our hiding place.

I grew up listening to Mom and her friends, drinking coffee around our kitchen table while they animatedly discussed which group of people was ruining our country and if former President Dwight D. Eisenhower was really a communist agent.

I never quite understood what all the fuss was about. All I knew was that I adored listening to my Dad talk about politics and preach. I loved memorizing the verses he gave me about fleeing evil and avoiding temptation. I believed the words he spoke to be true. For me, he embodied the Heavenly Father he taught me about.

I didn’t feel the same about my mother. After every church service, whenever I’d overhear her describe someone as a person who “loved the Lord,” the hair on the back of my neck would stand straight up. If she caught me rolling my eyes as she quoted scriptures, I knew I had it coming. As soon as we got in the car, she’d slap my face.

My mother hitting me wasn’t unusual. Quite often after one of the regular beatings she gave me, she’d make me kneel in front of her, as she reverently prayed, eyes closed, “Please forgive Diana, Lord. She doesn’t know how to respect or obey me.” Never knowing when she’d strike, I was constantly on guard.

I believed in God as a child and deeply felt Jesus was my friend, responding to an altar call when I was 6. But Mom smugly told me Jesus could never love a naughty, backsliding little girl like me. Because of that, I was never sure my salvation stuck, so I made at least half a dozen more trips down the aisle. My teenage years and early 20s did little to reassure me of God’s love. I didn’t want to go to hell. It seemed like a scary place. But when I was 25, hell found me anyway.

Death sentences

ON JAN. 7, 1988, after three weeks of hospitalization and testing, my father was diagnosed with AIDS and given six weeks to live. Three weeks later, my mother tested positive for HIV.

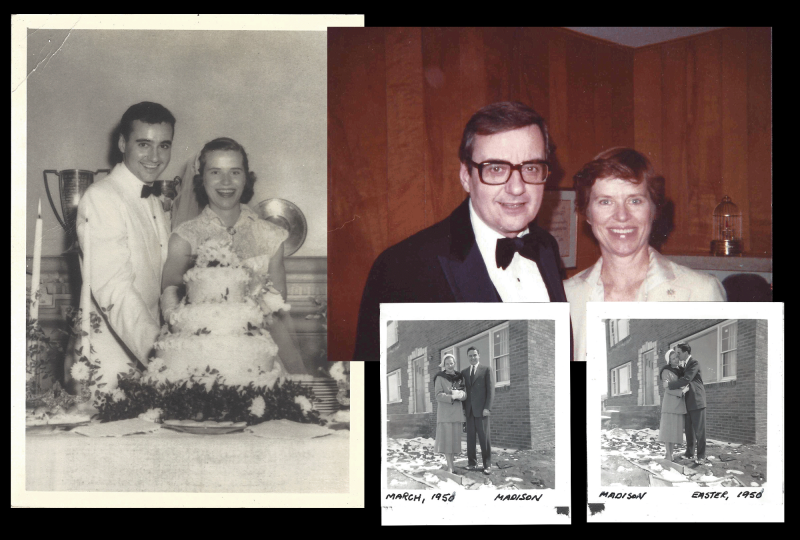

My dad — church leader, regular host of JBS meetings, and senior partner in Milwaukee’s largest law firm — had been living a double life. He had been having sex with men for more than 27 years and unwittingly infected my mother with HIV. My parents had six grown children, eight grandchildren, and had just celebrated their 38th wedding anniversary. I was their fifth child, newly married, and the mother of a 6-month-old son.

Overnight, our family gained modern-day leper status. My parents’ washed-in-the-blood church friends scattered like cockroaches when the lights came on.

Not much was known about HIV and AIDS in 1988, and rumors about how it spread were rampant: toilet seats, skin-to-skin, saliva. People magazine ran a cover story about a young woman getting it from her dentist. Tucked inside one of my mother’s journals, I found an erroneous newspaper article reporting the virus could live on doorknobs for three days. The “AIDS cocktail,” a combination of drugs highly effective in slowing HIV, hadn’t been invented yet; and the term “safe sex” was still new. At this time, AIDS was considered a death sentence. Everyone was afraid.

My mom was furious and swore she would never forgive my father. She wanted nothing more to do with him and kicked him out. Who could blame her?

I did. I blamed her for the entire mess. If she hadn’t been such a difficult woman, I wondered, maybe my dad wouldn’t have strayed. Maybe he wouldn’t be dying now.

As a kid you have to put your trust in something or someone, so I put my trust in my dad. As I grew older, I thought of him as my model for becoming a mentally healthy adult. He was my North Star.

Though shocked at what was happening to my family, my journalist’s instincts kicked in. I started taking notes and recording conversations. When Mom said she was going to the hospital to confront Dad about how he got infected, she allowed me to drop my recorder into her purse. It was only when I listened to it afterward that I learned she pulled a knife on him and tried to kill him.

Drowning in grief, I told God I didn’t believe anymore. If my dad could be such a liar, God was just one big, cosmic joke.

“If you’re real, you’re going to have to prove it to me,” I dared God.

diana_keough_.png

Loving hands

AFTER DAD WAS released from the hospital, he had nowhere to go. One of my brothers found him a spot in Caracole House in Cincinnati, one of the first AIDS group homes in the country. We changed my dad’s name to protect his anonymity and so my brother, who lived and worked in Cincinnati, wouldn’t be “outed,” as he said. Shame followed us everywhere.

Dad didn’t die immediately. His condition improved and he was able to move out of the group home. For the next two and a half years, he became a leader in the Cincinnati gay community, offering free legal advice and starting organizations to foster awareness of people with AIDS. He often shared his story publicly and appeared twice on a conservative national radio show, trying to put a “normal” face on AIDS and make it seem a bit less scary. No longer living a lie, he seemed comfortable developing deep friendships with other gay men.

These men were so kind to my father and to me whenever I visited. I enjoyed getting to know them and interviewed some of them, trying to understand my father, and them, better. As my father’s health declined, I watched men I would have been afraid to touch a few years earlier care for him: lovingly turning him over in bed, feeding him ice chips, and wiping his brow.

I was taught to love the sinner but hate the sin, but so many of the Christian leaders who said that also said AIDS was God’s wrath on homosexuals; they pushed for AIDS patients to be isolated and quarantined.

In one of my interviews with my mom, she strongly echoed these beliefs. I remember thinking people demanding quarantine wouldn’t lift a finger to help mom, given she, too, was now an AIDS patient.

Like a shoreline reshaped by a hurricane, my heart underwent a radical change now that AIDS had faces and names I knew so well. These men were now my friends and watching their slow, agonizing deterioration gutted me.

In the hours before his death, Dad, agitated and restless, repeatedly muttered my mother’s name, begging her to forgive him. We called Mom and asked her to speak to Dad, but she refused. So, we decided to lie and tell him she forgave him. He settled down immediately.

An hour or so later, he passed away with Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” playing on a loop.

new_keough_spot_1.png

Learning Grace

MEANWHILE, AS MY father came to peace with himself, my mother sold the family home and moved to the other side of Milwaukee, where she was embraced by a small, nondenominational women’s Bible study. Many of the women in this group spent time ministering in Texas prisons.

They invited Mom to Texas to meet death row inmate Karla Faye Tucker, who was sentenced to death for pickaxing two people to death while they slept. Tucker was said to have experienced a jailhouse conversion to Christianity and was now famous for her selfless ministry to fellow inmates, guards, and hundreds of visitors. Larry King interviewed her, as did Terry Meeuswen, co-host of The 700 Club.

“The most amazing thing happened to me,” Mom told me after her first visit to prison. “I met the kindest, most wonderful woman. She just loves the Lord.” She couldn’t stop talking about what a “wonderful Christian” Karla was, which struck me as particularly ironic given my mother’s staunch support of the death penalty.

I was skeptical, but over the next four years, my mother changed. She offered apologies without prompting, embraced me with a little more lingering tenderness, and let kind words flow. It was as though the bitterness that once consumed her was slowly evaporating, leaving behind a softened heart. Instead of dwelling on God’s judgment, she found solace in speaking of God’s grace, as if a weight had been lifted from her shoulders, allowing her spirit to soar with newfound freedom.

When Mom passed away on Aug. 1, 1994, six years after her diagnosis, I was holding her hand. The hours I had dedicated to interviewing her, delving into her pain, listening as she recounted tales of an absent father and the cruelty inflicted on her by her own mother and her brothers, tempered something within me. With each word she uttered, each tear she shed, compassion began to seep into the cracks of my heart, gradually eroding the barriers that once stood between us. As she took her last breath, the progress made on our shared path toward healing and understanding felt like a victory of sorts.

Her death broke me and left me rudderless. My marriage was in shambles, I was overeating, smoking, and drinking too much. Six months later, I entered that same Texas prison to meet Karla Faye Tucker, on a quest to see what Mom had discovered there. I expected to meet a phony.

As that last maximum-security door slammed behind me, Karla ran toward me, her arms open wide. It was my first exposure to people in prison, much less a person on death row, and I was frightened.

“You’re Diana,” Karla said, as she held me. “After all your mom’s told me, I feel like I know you.” My knees hit the floor and I began to cry. I couldn’t believe my Mom spent even a nanosecond talking about me, here, in this place, with this person who meant so much to her.

As I sat beside Karla, her hand clasping mine, I was captivated by her serene radiance, a luminosity, as if knowing God had forgiven her, she was able to lay herself bare and shed all pretense, leaving in its place profound peace and love. I couldn’t stop crying.

“God always brings you to a place where you’ll finally listen,” Karla said to me. “And for me it was really, really low. It was pretty low for your mom, too.”

“You’re so lucky,” I told Karla, sobbing.

“Lucky?” she asked. “Lucky, how?”

“Because you’re in prison and you’re so ... free. And I’m on the outside, walking around in a prison of my own making,” I said.

“Don’t be sad,” she said, wiping away my tears, “I know where I’m going. And so did your mom.”

It was here, in this moment on death row, staring into Karla’s face, that God met my bold dare head-on and became real to me.

Suddenly, those stories from the Bible that Dad taught me gained new meaning. One in particular came to mind: the tale of the woman caught in the act of adultery. According to ancient custom, she could have been subjected to the merciless punishment of stoning. But Jesus, there amid the crowd, offered a profound challenge: “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone.” And in that charged moment, the stones slipped from their hands, one by one, and the crowd dispersed. Jesus didn’t condemn this woman, or scold her, muttering, “I hope you’ve learned your lesson.” He simply said, “Go and sin no more.”

I, who had always fancied myself as forgiving and accepting, like Jesus, came face-to-face with a startling realization: I was more like those in the crowd ready to stone the woman. I was quick to cast judgment upon others, while conveniently sidestepping my own flaws of pride and conceit. The condemned woman walked away from her encounter with Jesus enveloped in the boundless grace and love of God. I was humbled, knowing I still had much to learn about true grace and forgiveness.

In the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), the younger son, lured away by desire, squanders his inheritance in a reckless pursuit of pleasure, only to find himself impoverished and alone. Yet, on his return he is met not with judgment, but with the open arms of a father overflowing with unconditional love and ready to throw him a party. The older son, who had faithfully stayed home, angrily refused to go to the party.

Reflecting on this story, I am fully aware that I am that elder son, struggling to grasp the limitlessness of God’s grace. His heart, like mine, was hardened by resentment and envy, and remained closed to the transformative power of forgiveness, unable to fathom the depths of his father’s compassion and love.

I want one thing to be clear: I don’t seek to diminish the gravity of Karla’s actions, nor overlook the pain inflicted upon her victims and their loved ones. Yet on death row she became a beacon of hope — a testament to the limitless capacity of grace to heal even the deepest wounds. The world witnessed her profound metamorphosis, a shedding of her old self and a fervent embrace of redemption’s promise before she was executed on Feb. 3, 1998.

On the weekends I spent with my dad before he died, he would ask me to accompany him to nearby Calvary Episcopal Church. In the dim light of the sanctuary, he’d take his place in the back row, tears streaming down his weathered cheeks, his emaciated frame trembling with emotion. When I mustered the courage to ask him why he cried, he offered a simple, yet poignant response: “I just can’t get over the fact that God could forgive someone like me.”

On a recent Sunday as I sat in church, letting the music wash over me, eyes closed, the words of the song brought my parents to my mind. “Oh, the overwhelming, never-ending reckless love of God.” Love. God’s love is transformative.

A lump caught in my throat as I thought about my parents’ courage in the face of death, their faith journeys, their redemption, and the ways God changed them. How my dad died knowing God had forgiven him; how my mom was able to finally forgive my Dad and died in peace. When my mom and dad died, they were not the same people. And because of God’s grace, I too, am no longer the same.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!