I MET JULIA ESQUIVEL for the first time in Mexico City, on a rainy afternoon more than 30 years ago, after my 2-year-old son, Abraham, and I crossed the exasperating metropolis by bus and clanky train. Flustered and dripping, I knocked on the door of her tidy home. Esquivel lived in exile, far from her beloved homeland, Guatemala. Henchmen in the service of Guatemala’s military rulers had pursued her relentlessly until at last she fled. I, a young, earnest Canadian, was traveling the northern continent, from Montreal to Costa Rica, preparing to write a book, recording the voices of women—such as Esquivel—scattered in this Guatemalan diaspora.

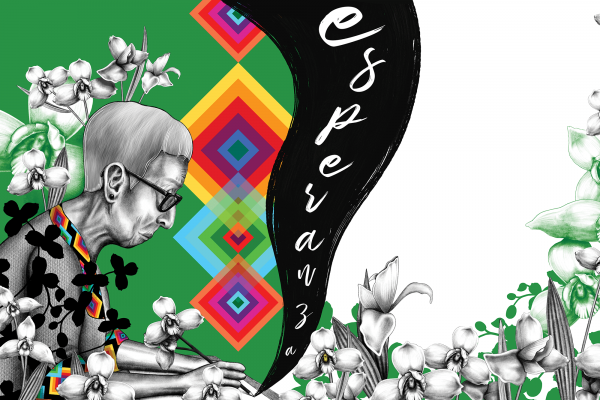

Esquivel was slender and small, silver hair framing her delicate, elegant face. She ushered us into her house, where we sat on cushions on the floor, drank hot tea, and read stories about St. Francis and a very bad wolf. We talked while Abraham toddled around, and we prayed. That was Esquivel: determined to pray through hurricanes, from the unimaginably large to the very small.

Our friendship spanned the decades. She was to become one of my greatest teachers. Because of Esquivel, who passed away last July, I—raised in a radically atheist household—am now a Christian. Esquivel first cracked open faith for me, showing my young rebellious self that the strongest power for transformation, for individuals as well as nations, came from a place of stubborn grace, a grace, like hers, that never surrendered.

The way a country treats its children

JULIA ESQUIVEL WAS born in 1930, in the western highlands of Guatemala, to a middle-class, progressive family. She was a surprise daughter to an older couple who had been told they would never have children. She grew up treasured. At 7, she said, she found herself before an image of Jesus on the cross; her heart broke with compassion for his suffering.

In 1947, Esquivel became a teacher, and several years later she traveled to Costa Rica to study theology. For a while, she tried on the idea of becoming a minister—first in the Presbyterian Church. She quickly found that the church refused to ordain women. From that time forward, she considered herself a Christian without a particular denomination; she called every imperfect church her home. She worshipped with Mennonites, Episcopalians, and Catholics.

Like people in any family, she quarreled with her siblings: other church members and, particularly, leaders. Young and filled with passion, she actually expected the widows and orphans to be cared for and the poor to be attended to with compassion. She believed this concrete truth: Jesus Christ made room for everyone at the table, starting with those who had been rejected by the world. Time and time again, she clashed with polite church institutions that did not embody what she believed were gospel values: inclusion, justice, the sharing of goods and gifts. Early in her young adulthood, Esquivel decided she would never marry, saying that even a good marriage would have stifled her.

Read the Full Article