IF YOU WOULD be so kind, I’d like for you to do an experiment with me. Think about a famous work of art, a painting so widely considered Important and Valuable its status could never be questioned. Maybe you’re debating between “The Starry Night” or “Mona Lisa.” Maybe you’re considering something else entirely: Monet’s endless assortment of water lilies, for example. Good. Hold the image in your mind and recall, if you can, the work’s textures, its colors and its moods. Do you like the piece? Do you remember when you first encountered it?

Now, having answered those questions, imagine that someone has stolen it. This mysterious person explains that they are holding the painting hostage until works falsely attributed to the artist in question are exposed as fraudulent. They sign their manifesto with the words, “You will come to agree with me.” What would that do for the public imagination?

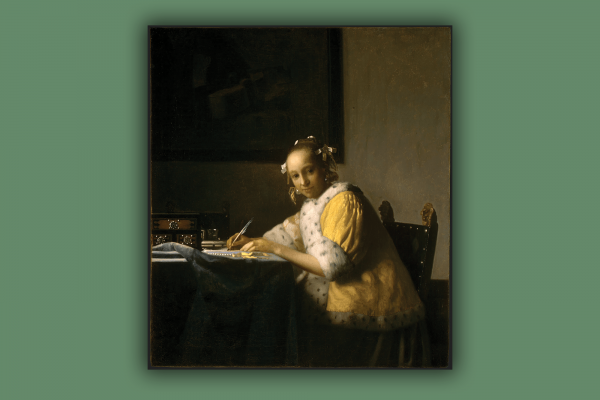

Blue Balliett explores this question in her 2004 novel, Chasing Vermeer, and though its main characters are sleuthy sixth graders, I find its basic premise has much to offer even to jaded adults (see: me). A Vermeer painting on its way to the Art Institute of Chicago—“A Lady Writing”—disappears mid-journey, and the thief posits a series of challenges to art historians and the broader world. Petra and Calder, two intrepid University of Chicago Laboratory School students, find themselves caught in the painting’s thrall and, through a series of dreams and coincidences, set out to find the “Lady.” But they’re not alone.

In the blink of an eye, Vermeer becomes a subject of constant debate. So-called “unqualified” people chatter in taxis and restaurants about whether Vermeer’s later paintings actually bear a resemblance to his more famous (and luminous) work, “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” Petra and Calder’s class compares brushstrokes on various Vermeer reproductions, taking a vote on which paintings should be considered legitimate. Mutiny descends on the art establishment. Mutiny, yes, because a delicate painting has vanished, but also because a branch of knowledge that is shrouded in esotericism and fancy degrees is now under scrutiny. By stealing “A Lady Writing,” the thief has returned the public’s right to have opinions about it.

When I first encountered Chasing Vermeer as a 9-year-old, I was thrilled. Nothing sounded better than mysteries solved with friends. It was a simple and pure love. Revisiting the book now, many years later, I am struck by how much of the story still thrills me. Balliett wrote my favorite alternate dimension into being, where art isn’t a stuffy thing behind glass but a conversation hundreds of years in the making.

A few years ago, the National Gallery of Art in D.C. opened a show on Dutch portraiture featuring several loaned Vermeers. Unsurprisingly, the line for the exhibition snaked through the main atrium. When I finally got into the room, a fellow visitor struck up a conversation with me and we talked about the political (and gendered) nature of portraits. I’m sure a curator would have been dismayed to hear us, but it didn’t matter. We were, in our own ways, chasing Vermeer. And, looking at the knowing expression of “A Lady Writing,” I have a feeling he wouldn’t mind being found.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!