"Bloody Sunday" stands out as a watershed event in the struggle for civil rights in the South. Six hundred civil rights marchers were beaten by state troopers and sheriffs deputies as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama in March 1965. International outrage at such blatant displays of police brutality forced President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Congress to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Selma is once again the setting for a battle that promises to have implications as serious for the future of race relations in the United States as "Bloody Sunday" did 25 years ago. And still the issue is power -- who has it and who wants it -- except that the social context this time is education.

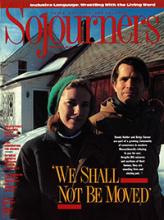

Dr. Norwood Roussell, Selma's first black school superintendent, was fired on December 21, 1989, by the school board. The vote to dismiss Roussell was split along racial lines, with blacks voting to keep him and whites voting to get rid of him. The vote triggered a walkout by the four black school board members, daily demonstrations by both blacks and whites, a boycott of Selma's 11 public schools by black children, and a five-day sit-in at the high school by black parents. When classes resumed, Selma sheriffs deputies and Alabama state police surrounded the schools to ensure order.

"This is not a matter of my performance here," said Roussell. "This is a matter of who is going to be in control. Whites have final say on everything in the community -- including the schools."

Selma's 11 public schools are 70 percent black, yet its school board is controlled by whites, six to five. The school board members are appointed by the city council, which is controlled by whites, five to four. The city council and the school board are backed by powerful white Mayor Joseph T. Smitherman, who was mayor of Selma during "Bloody Sunday."

Read the Full Article