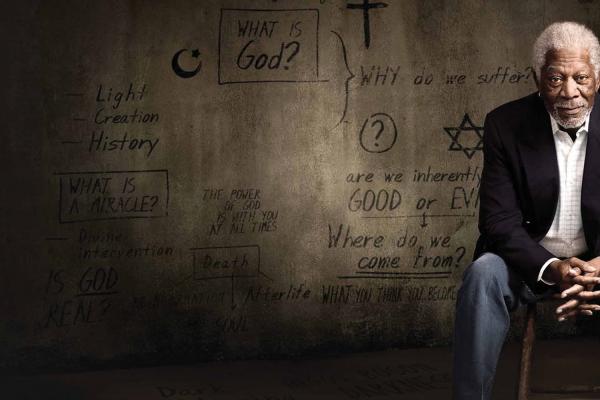

FEELING STRESSED BY CURRENT EVENTS, weary of ugly public discourse and the contentious sniping among even those who claim the same political party or faith? Maybe what you need is context—a look at the sweep of history and the enduring mysteries of existence. It’d be nice if there were a guide. Perhaps someone with a rich, velvety voice and calm presence to accompany you to far-off places and times—even better, to take you there on a private jet—and to not only ask deep questions but arrange for experts to posit answers.

You may be in luck: The Story of God is a six-part documentary series scheduled to air weekly on the National Geographic cable channel beginning on April 3. Actor, producer, and Story host Morgan Freeman travels the globe to glimpse how some religions (and a bit of modern neuroscience) attempt to answer our big human questions. Is there life after death? How was the universe created? Will the world end, and how? Who is God? What is the root of evil and how has our idea of it changed over time? Are miracles real?

(Let’s just get this out of the way now: Yes, Freeman has played God in two feature films, Bruce Almighty and its sequel Evan Almighty. No, he is not reprising the role in The Story of God.)

Given the enormity of the task Freeman and the other producers set for themselves—wrestling with theological conundrums, including some perspective from ancient beliefs and each of the five major world religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism), shooting in 13 countries, and whittling all that footage down to six hours total for airing—they did admirable work. It’s impossible to go deep or broad into a religion within those kinds of constraints, but the threads of history and theology presented, and the experts presenting them, are interesting and legitimate. There are bits of melodrama in the framing of Freeman’s quest and in some of the dramatizations of historic events, but this is edutainment TV, not a graduate school seminar.

Read the Full Article