And as he was praying, the appearance of his countenance was altered and his clothing became dazzling white.

-- Luke 9:29

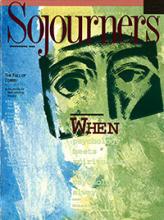

In considering from a religious perspective the Kremlin coup's hectic rise and fall, one should be aware that the day Gorbachev's removal was announced also happened to be a day of particular importance in Orthodox Christianity: the Feast of the Transfiguration.

For those attuned to the church calendar in the West, this comes as a surprise; they had marked the same event in Christ's life nearly two weeks earlier. The problem is a disparity of calendars. The Old Calendar, established under Julius Caesar in the mid-first century BCE, is still used within the Russian Orthodox Church. Thus while every newspaper declares it is August 19, the church turns the page to August 6.

As the junta was preparing for its first (and, as it turned out, only) press conference in the Kremlin, the gospel being chanted in surrounding parishes described the revelation to Peter, John, and James of Christ's true face. The icon being kissed that day by the faithful entering every Russian church shows the three disciples struck down by blinding light.

In the future Russian believers will link the Transfiguration with the day Russians recovered their own true face -- not the familiar face of acquiescence to czars and political bosses which marked them from the days of Ivan the Terrible through Stalin and Brezhnev, but a face that can confront an army.

Among the more surprising indications that not only the Russian people but the Russian church was turning a corner was the appeal made by Patriarch Aleksi at a time when it seemed likely that massacres were going to happen outside the Russian Parliament and wherever democratically minded citizens dared to confront the military.

Read the Full Article