PROFESSIONAL-GRADE paint brushes are about 10 inches long, with enough heft to balance in one hand, allowing the artist the control necessary to usher an idea into paint-and-canvas reality.

For more than 20 years, Ndume Olatushani used brushes with handles that were mere stubs. Fearing that a full-length brush could be sharpened into a knife, officials at the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville, Tenn., cut them to about a third of their original length. To paint, Olatushani wet magazines and rolled them tightly around the broken ends. Once dry, the hardened pages worked almost as well as regular handles. Olatushani would then prop a canvas on his knee—easels weren’t allowed and his cell barely had space for one anyway—and paint.

The guards didn’t want Olatushani to have a weapon, but he did: The magazine-handled brushes kept him alive, bringing to life the world of his mind decades before he was freed from the monochrome world of prison.

“Art was freedom to me,” Olatushani explained. “I was literally walking in the shadow of death, but I was able to escape into the world I wanted, that I was able to create inside my head. Being able to do that made it possible for me to come through the other end.”

A happy medium

In 1985, after a seven-day trial in which prosecutors withheld evidence, a key witness lied, and an alibi was overlooked, Ndume Olatushani, then known as Erskine Johnson, was convicted of a murder that had been committed two years before. It took the all-white jury less than two hours to sentence him to death.

Thanks to the efforts of lawyers who took on his case pro bono in the ’90s, Olatushani’s death sentence was overturned in 1998. And after nearly 27 years imprisoned for a crime he did not commit, he finally walked away from the Shelby County Jail in Memphis on June 1, 2012.

In prison, each day was dominated by guards, confinement, and an existence so rote Olatushani could tell what day it was by the breakfast pushed through the flap in his cell door. Now, three years after his release, the din of clanging doors has been replaced by the pleasant hum of daily life. As I talked with Olatushani in his living room, his niece cooked veggie burgers in the kitchen while his great-niece watched over her infant daughter, who cooed and squealed. Outside, a neighbor’s lawn mower whirred through the languid July afternoon.

Olatushani met his wife, Anne-Marie Moyes, while she was working with a nonprofit advocating on behalf of death-row inmates. The two became friends, eventually fell in love, and were married shortly after Olatushani’s release. The walls of the Nashville bungalow they share are adorned with paintings of dark-skinned men and women wearing bright kangas and turbans. In the foyer, a young boy wrapped in a yellow cloth carries a bundle of reeds. In the dining room, three women gaze and point in one direction, as if starting a journey together. Two carry infants; another holds a bright umbrella against the sun’s glare.

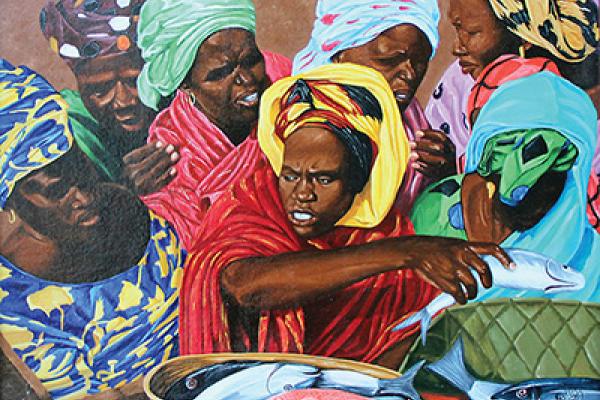

A painting of several women projects a less hopeful view. They are hovering over food baskets, scowling. One woman snatches a fish from a meager pile, the fish bending around her long fingers with the motion. “This one is about scarcity and stress,” Olatushani explained. “It’s called ‘Food Desert.’”

The paintings are vivid and precise; life seems to flow through the characters. Their eyes suggest memories, stories, and hopes; their clothing wrinkles with movement.Veins show on their hands. I wanted to lean in and ask these people where they were going, how they remained strong, if anyone knew how to make the fish last.

A visitor who didn’t know better might assume these works were purchased at a posh gallery. But Olatushani, who rarely traveled beyond his hometown of St. Louis before being extradited to his trial in Memphis, painted them all during the two decades he was on death row. He has continued painting ever since, but he keeps the death row works up in his home.

“It’s almost a pleasant reminder of my whole struggle,” he said. “Being on death row for 20 years or being locked up, period, is a stressful environment. It’s oppressive, and all these different things serve to dehumanize and break people’s spirits. For me, these paintings are representative that, even under those circumstances, I refused to be bent or bowed and was able to create, for lack of a better word, a happy medium.”

The power of self-expression

By Olatushani’s own admission, he “couldn’t draw a crooked line straight” as a kid. And he only began painting in prison because he hated a portrait he’d commissioned a fellow inmate to draw. “It could have been [a picture] of you,” he said, dryly. I laughed, because I am both a woman and white.

So with “nothing but time and a little space” to develop his talent, Olatushani taught himself to paint. But now that he is out of prison, Olatushani is passionate about helping young people discover their talent before they end up as he was: locked in a cell with all the time in the world.

Since his release, Olatushani has worked with the Children’s Defense Fund, using creative expression to educate young people at schools, churches, and community centers in Nashville about what the CDF calls the “Cradle-to-Prison Pipeline.” Through a six-week curriculum he created, Olatushani helps youth understand the systemic forces, such as privatization of prisons and school discipline policies, that land a young person in court instead of the principal’s office. After the students watch and discuss films such as Slavery by Another Name and Kids for Cash, they start making art.

“I’m trying basically to inform and educate them about these systems that are operating around them. People are too quick to point fingers at young people and say how bad they are, when really it’s not the kids that are bad, it’s the systems that are operating around them—around us I should say—that are really bad,” Olatushani explained.

With Olatushani’s guidance, the youth become artists, creating murals, portraits, and puzzles—always projects that emphasize smaller pieces gathering into a larger whole. This past school year, young people in Olatushani’s program took on their biggest exhibit yet: the Cradle-to-Prison Pipeline School Desk Project. Each group at each separate location was given a prison jumpsuit and a school desk to arrange and decorate as they saw fit. Once all the groups created their desks, they were arranged in rows as a “class.” The installation has been displayed at a number of galleries in the city.

It was summer when I met with Olatushani, and his students were out of school, but a few of the desks were stored upstairs in his home. Their variety is striking: intricately graffitied jumpsuits; jumpsuits with money coming out of the pockets; a jumpsuit handcuffed to a Bible; a jumpsuit attached to actual working circuitry representing an electric chair. The emptiness of the prison clothes, stiffened with a fabric treatment to allow them to “sit” at the desks, gives a haunted impression, as if their occupants have been erased by greed and power.

And yet Olatushani has seen the empty jumpsuits bring his students to life. “A lot of kids start out, ‘Naw, I can’t do that. I don’t know how to paint; I can’t draw,’” he said. “You kind of drag them into it, but then, once they actually get into the project and begin to see the work that they’re doing in relation to the kids around them, they just really get into it and get engaged. They begin to not only see it coming together, but they begin to see that they are part of something larger than, you know, them.”

Olatushani wants these teenagers to tap into the power of art and self-expression before it’s too late. “I tell people that I was an artist before I was sitting on death row. I just didn’t have the time or space or intervention that would allow me to explore my creativity or express myself the way I do now. I didn’t have to be sitting on death row for that to come out. That just happens to be where I was.”

In prison, art became a way for Olatushani to rebel against the system that held him for nearly three decades. As long as his family continued to order supplies from a prison-approved art catalogue and send them to Olatushani, he was free.

“I knew was that I was freer than a lot of the officers that were coming in there every day,” Olatushani said. “I knew who I was. I knew what I was. I knew what was going on around me, as opposed to some of these people who are just kind of a cog in this wheel ... A bunch of them were miserable. That’s the thing that I was free from that they weren’t. [Art] was this thing they couldn’t take from me, and they certainly couldn’t control it.”

In the face of all these odds

Now free in both mind and body for more than three years, Ndume Olatushani continues to paint. His brushes have proper handles. He’s learned to work while standing at an easel. And though the content of his art is different, its vivid, lifelike style remains. “I’m not the type that, as an artist, I can create this abstract stuff,” Olatushani said. “I still want to have my artwork reflect what’s going on around me, even in terms of the work that I’m doing with young people and the importance of just wanting to be a facilitator, trying to get young people through to the other side.”

One of the first things Olatushani told me is that he has been “happy as a lark” since winning his freedom, and our subsequent conversations bore that out. He joked easily and mentioned that his even-keeled temperament helped him emerge unscathed by his unjust incarceration.

However, some anger is good, and he confessed that he does get angry when he thinks about how the systems and prejudices that landed him in jail are still in motion. So he does what he can: He teaches and paints.

During an afternoon together at a coffee shop, Olatushani ate a piece of coconut cake piled with frosting (he had requested the “sweetest dessert in the case”) and described a painting he calls “Winds of Change,” where four figures huddle together on a green mountaintop, features obscured by their blowing clothing.

“The idea was that in the face of all these odds, they had climbed a mountain out of a valley,” Olatushani said. “Once they got to the place where they needed to be, they still had all this wind in their face, all this stuff, which is symbolic of anything that is holding you down. But rather than being beat back down the mountain, the idea is they turned their back to the wind and held the ground that they were able to gain until they were able to turn around and walk and fight some more.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!