WHEN DANIEL and Philip Berrigan, A.J. Muste, John Howard Yoder, and a handful of Catholic radicals gathered in 1964 with Thomas Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky for a retreat concerning the spiritual roots of protest, the intercessions of that meeting, I am convinced, not only seeded a movement but summoned my vocation.

Four years later when Daniel and Phil Berrigan and seven others entered the draft board in Catonsville, Md., removed 1A files and burned them with homemade napalm, those ashes too would eventually anoint my pastoral calling. October marks the 50th anniversary of the trial of the Catonsville Nine. Released in February 1973 after 18 months in the federal penitentiary at Danbury, Conn., Daniel Berrigan came to New York and taught the Apocalypse of John when I was a student at Union Seminary. Full disclosure: He became to me not merely teacher, but mentor and friend.

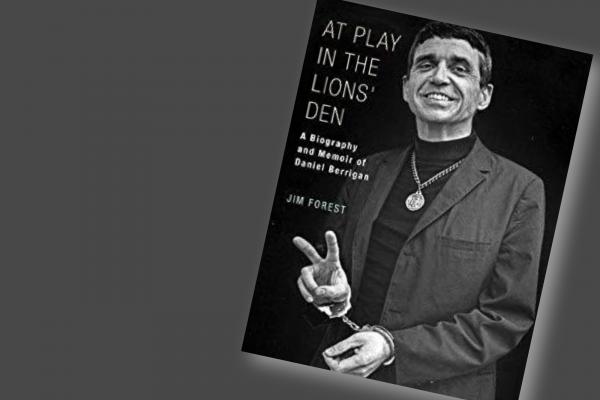

In the year following Dan’s death (April 30, 2016), Jim Forest undertook the heroic literary effort of writing At Play in the Lions’ Den. Perhaps he had a running start. Three things of note up front. One is that Forest’s own life is inextricably tangled with Berrigan’s. He was, for example, editor of The Catholic Worker when Dan first appeared there, was part of the 1964 retreat with Merton, and responded to Catonsville by joining others in a draft board raid in Milwaukee within the year. So, like the Acts of the Apostles, there are whole sections of this book written in the first-person voice. Or betimes, Forest just peeks from behind the elegantly researched narrative to lend a knowing detail. This is a risky wire act. Don’t fall into self-aggrandizement (his genuine modesty saves him that) or the net of hagiography. And best to name this from the start, in the subtitle: “biography” and “memoir,” a difficult art Forest has mastered.

Read the Full Article