NONVIOLENT DIRECT ACTION is a relatively new invention — though prefigured by the Cross, it was Gandhi, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and a million others whose names we don’t know or remember who introduced this technique to us over the course of the 20th century. There’s no handbook for how it’s done, and no West Point equivalent — which means that we largely proceed by trial and error as we try to move the conscience of the world. We make it up as we go along. Which is fine, but you must be honest about what works.

Over the last year, one tactic that climate activists have tried is attacking cultural works — iconic paintings, right up to the “Mona Lisa,” and great shrines of humanity, most notably Stonehenge. They’ve been responsible, figuring out ways to do minimal damage, and perhaps such methods were worth a try: When you’re losing, you throw Hail Marys. And the people who carried out these actions clearly should not be subject to ridiculously punitive sentences.

But my sense is that the dominant reaction probably indicates this isn’t a fruitful strategy — there’s something about attacks on artistic icons that seems to raise the hackles, even of those sympathetic to the cause. At the very least, the debate usually ends up being about the tactic, not about climate change. One reason may be that the targets are a little too far from the actual villains — it’s oil companies, not oil paint, that are the problem.

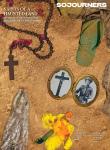

But the very strength of the negative reaction should suggest a different possibility: We could use culture as a nonviolent weapon against those institutions that we must face down. I went to jail this summer for a sit-in outside Citibank headquarters in downtown Manhattan. Citi is one of the biggest funders of fossil fuel expansion on the planet. It was a powerful action because organizers staged a mock funeral, led by a bagpiper who slowly circled the block; the wail of the pipes, so associated with mourning, changed the whole atmosphere. (And when he went into “Amazing Grace” I started to cry.)

Even better, a few weeks later a professional cellist, 63-year-old John Mark Rozendaal, lugged his instrument on the subway to the bank, and started playing — blocking the door to the bank with a performance of Bach’s “Suites for Cello.” The police eventually hauled him away, but not before he’d gone quite viral. And not, I think, before he’d reminded people of one of the reasons we need to care: Because the human societies now under threat from climate change have produced majestic works — paintings, sonatas, shrines. These are part of what we defend when we try to slow down the civilization-crushing rise in temperature — and so it is natural that we should use them, not deface them, in our defense.

The police brought Rozendaal’s performance to an end halfway through — but his is a tune that anyone can pick up and carry on.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!