Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

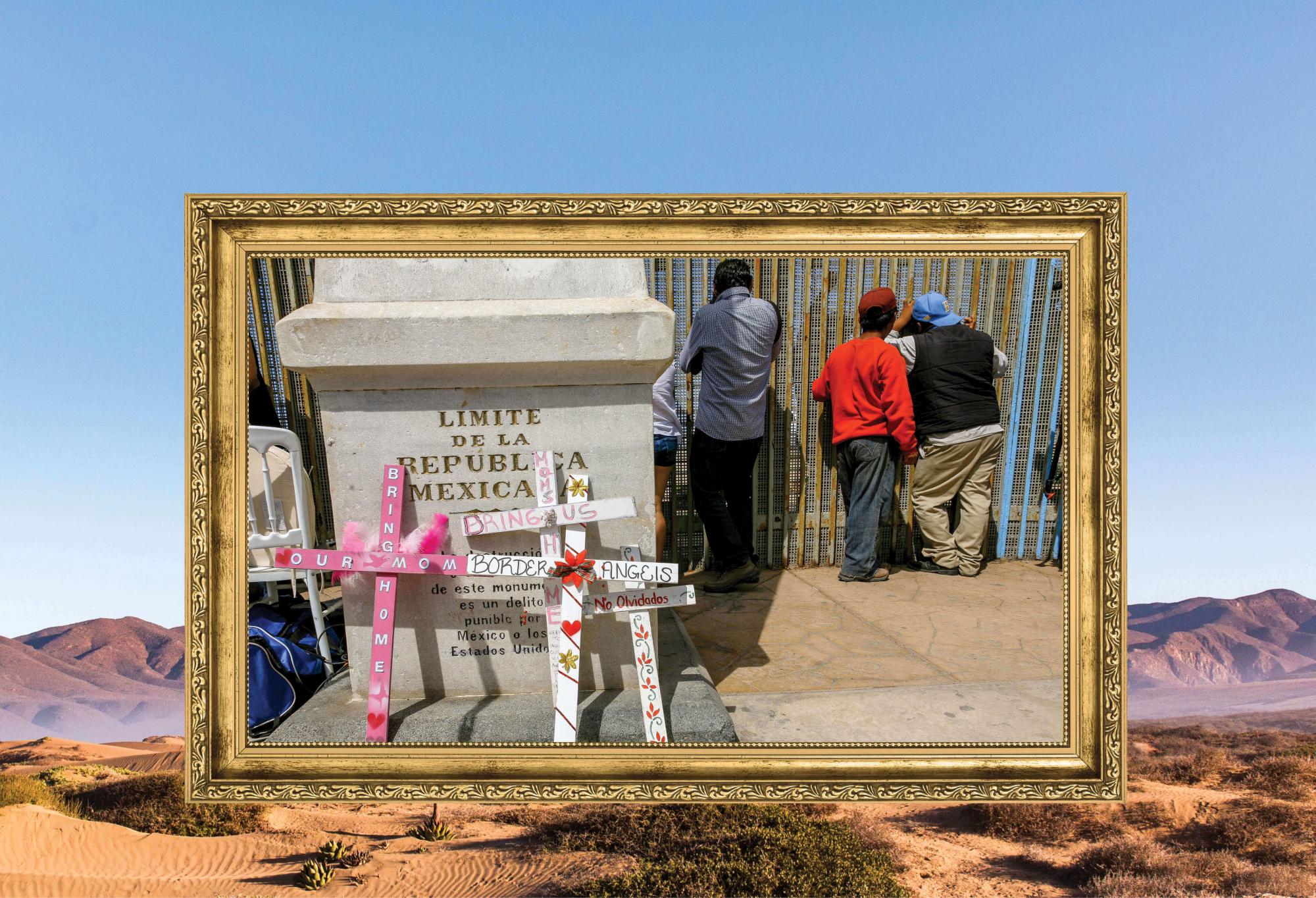

Photo Beto / iStock

IT'S A GRAY, mid-May morning in Panteón Municipal #1, a city cemetery in Tijuana’s Zona Norte neighborhood. Alberto, the gatekeeper, saunters down a rocky pathway lined with palms, jacaranda, and gravestones to a prominent, red brick chapel, built over the tomb of one Juan Castillo Morales.

The shrine is covered wall-to-wall with candles, flowers, and plaques with names and messages of thanks to “Juan Soldado” (Juan the Soldier), as Castillo is known. Amid the array sits a stylized bust of a young soldier, resplendent in military attire, this morning bearing a black rosary and a blue-and-white Los Angeles Dodgers snapback hat.

The shrine is one of many unofficial memorials where loved ones remember lives of immigrants lost along the U.S.-Mexico border. From chapels erected around the graves of unofficial saints such as Castillo to digital memorials people carry with them into the desert to the crosses, flowers, and other mementos left along the border boundary itself, these monuments not only pay tribute to the individuals lost but bear witness to the ubiquity of death — and faith — in America’s southwestern borderlands.

Rosalba Ruiz-Hernández, a 46-year-old mother of five, stands in the shrine. Ruiz-Hernández, originally from the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, was deported back to Tijuana after her own failed attempt to start a new life in the U.S. Two of her grown children still live in Long Beach, Calif., near her former husband. They are undocumented, she said, but they make a living. Two others are in Tijuana with her. Matías, her middle son, died in the desert on his way north to join his siblings in Southern California.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!