I WAS VISITING my sister and niece in Maine with my middle daughter when we learned that Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon died. Our aunt in Oakland sent the obituary to our mom in Ohio, then Mom texted us: “Thought immediately of you both and all that she and her music meant to us. Long, lovely memories.”

Even in the news of her passing, Reagon, the founder of the celebrated music ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock, was connecting women across generations, geography, religious, and racial categories. The music of Sweet Honey helped my mom, a white Quaker woman and Methodist pastor from rural Ohio, find her voice. It also shaped my sister and me as biracial Black women growing up in Washington, D.C. in the ’80s and ’90s. I took a course from Dr. Reagon during my senior year in high school. I never saw her again. Waves of grief and gratitude washed over me.

The day we got the news, we woke in a tent after camping near where the sun rises first over North America. As we drove past towering pine trees, taking in the news of one more passing — each death stirs up the sadness of all the other losses and more to come — my sister and I played our favorite Sweet Honey songs. We sang along to Reagon’s “I Remember, I Believe” from the 1995 Sacred Ground album: “My God calls to me in the morning dew / The power of the universe knows my name / Gave me a song to sing and sent me on my way / I raise my voice for justice, I believe.”

Later that evening as I rinsed my bare feet in a salty harbor, I stepped on something sharp, maybe an oyster shell, puncturing the middle of my foot. The pain went deep. As the blood flowed, I joked that this could be my stigmata. My sister and niece ran for the car and my teen daughter stayed by my side.

My daughter began to sing. We sang together as we waited. Our singing didn’t dull the pain; it transformed it. For a few moments, our harmonies joined the moonlight and the water. My child and I tapped into the power Reagon lived by.

“The power in her voice was (and is) an old power,” civil rights leader Rosemarie Freeney Harding wrote about Reagon. “It is a power of trees and turn-rows, of balms and boulders, of aching and making and aching some more. And it is the power of family, of our lacing and unlacing our lives, of our belonging to each other and to those who came before us and to those who left too soon.”

In her 81 years, Reagon was a singer, activist, mother, composer, historian, curator, and community builder who dedicated much of her work to passing on wisdom she gathered through oral history and song. Reagon called herself a “songtalker,” building community by gathering people around the sound of her voice. Her songs about everything from segregation, apartheid, sexual violence, U.S. policy against Haitian refugees, police brutality, greed, and labor rights to love, parenting, laughter, and joy offered generations of activists a vocabulary to challenge injustice around the world while keeping our souls nourished.

She also sang, preserved, and modified the songs of her childhood in south Georgia: songs of work, worship, struggle, and liberation that were so much part of the air around her that she thought of them less as songs than as evidence of community.

“The song exists as a way to get to the singing,” she said in an interview with her longtime friend Vincent Harding, “and the singing is not a product. The singing exists to form the community. And there isn’t anything higher than that that I’ve ever experienced.”

“The teachers of my sound are moving on,” she wrote in her 1975 song “They are Falling All Around Me.” Inspired by “Breaths,” a poem by Senegalese Wolof poet Birago Diop, Reagon wrote that song for the ever-growing list of people who had influenced her and had passed away. Her response to their deaths was to live with deeper purpose: “It is your path I walk / It is your song I sing / It is your load I take on.” Later, Ysaÿe Maria Barnwell, another longtime member of Sweet Honey, wrote “Breaths,” drawing almost directly from Diop’s same poem. Sweet Honey taught me to hear our departed loved ones in “the fire ... a woman’s breast ... in the voice of the water.” It is up to us, the living, to keep listening.

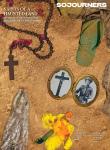

blackhoney.png

Songtalking

SWEET HONEY IN THE ROCK, founded in Washington, D.C. in 1973, was famous by the time I started attending their concerts in the ’80s with my mom and siblings. The group still exists and more than 28 women, including sign language interpreters, and a male instrumentalist, have been part of the ensemble over the decades.

In the ’80s and ’90s, I saw them at free festivals and sold-out performances at Howard University, where Reagon earned her Ph.D. in history. Their shows felt like the best version of church; audiences became congregations where everyone sang and belonged. After a concert, I asked Reagon about her career, and she told me she taught history at American University. The next school year, through a program that allowed public high school students to take free college classes, I signed up for her graduate-level seminar on American slavery.

I could hardly believe it when Reagon called me on the telephone soon after I enrolled. She asked about my course load, my extracurriculars, and my motivation for taking her class. I told her I wanted to learn from her. She gave me some wise advice: Drop that course and enroll in an art class to feed my spirit. She encouraged me to take her spring course on 20th-century African American culture the next semester. I followed her advice and took ceramics that fall. (I went on to choose art with a concentration in ceramics as my undergraduate major.) Reagon pointed me toward a path of centering, community, and balance, one I still strive to walk.

In the spring of 1996, I took the Metro up to Tenleytown-AU to sit each week within the sound of Dr. Reagon’s voice. Those classes were like being beside a deep well. In 1994, in partnership with the Smithsonian, she released the National Public Radio series Wade in the Water, tracing the sacred power of four centuries of African American music; as her student, I got to soak up the overflow. Reagon’s lectures were punctuated with perfectly timed songs echoing voices from pre-slavery through the present. She didn’t just talk about her organizing as a founding Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

Freedom Singer and leader in the Albany Movement, she sang the songs that moved beyond prison walls and helped her claim the power of her voice. Her lessons in culture-making were lessons in power, liberation, and agency.

Reagon taught how leadership, followership, and being an individual within a group are important for a healthy democracy. She also spoke about this in a conversation with Vincent Harding for the Veterans of Hope oral history project, preserving the voices of “elder activists.” She emphasized the importance of a “congregational style where the individual does not have to disappear, and it does not operate as an anti-collective expression.”

Reagon taught me how many of the popular freedom songs, such as “We Shall Overcome,” were originally sung in the first-person singular: “I Shall Not be Moved” and “I Shall Overcome.” I learned from her that it is important to remain an individual even in community. We can diffuse responsibility and sometimes dissolve a sense of self. What is it that I will bring to the conversation, potluck, or meeting? What is it that I believe? A healthy I is not against community.

A few years ago, I met writer Danielle Amir Jackson who, at the time, was editor in chief of The Oxford American. Jackson took Reagon’s graduate-level seminar in slavery (the class I did not take) while she was a sophomore at American University. She too remembers Reagon singing in class to demonstrate the sonic fusion between African and European folkways to form uniquely American sounds and traditions.

“It really imprinted on me how polyglot and cosmopolitan and multicultural American sound is,” Jackson said. “Dominant narratives are about cultural segregation. That wasn’t really the case. She really demonstrated that in a way that I could never believe in any kind of artistic segregation. She really helped land the lesson.”

Reagon also influenced Jackson’s life choices. Though she asked Reagon to write a letter of recommendation for law school, Reagon instead encouraged Jackson to pursue a life in the arts. “Dr. Reagon was one of the people who gave me an example to follow, or just other options besides kind of traditional, ‘Get a great job with the federal government kind of thing,’ which is what I thought I needed to do and was intentionally intending to do even up until senior year.” Reagon lived in the same neighborhood as one of Jackson’s friends and Jackson observed how much community meant to her teacher. Reagon taught her “a lesson in life and belonging, picking a place to belong to as an adult.”

Eileen Findlay, a professor and department chair for the department of critical race, gender, and culture studies at American University, was a student at Oberlin College in the 1970s when she first heard Reagon’s voice at a Sweet Honey in the Rock performance. Years later, she attended Berkshire’s Conference on Women’s History in 1992 and heard Reagon present as a historian. “Her historical narration about the power of searching for the voices of silenced people throughout history, of overturning our assumptions about who is on the margins and who is actually at the center, and interweaving that with constant song, and then saying, ‘Come on now, you do it too!’” left a lasting impression on Findlay. “Everyone was just on their feet and weeping. It was the most extraordinary historical experience I’ve ever had in my life. She held us in the palm of her hand and broke open our hearts and then made them whole again,” Findlay recalled.

“She was not just a feel-good person at all,” Findlay was quick to add. “She was a challenger, and she challenged everyone there [at the AU history department] to rethink what we understood was not only appropriate narratives of history and the meaning of history, but where history was expressed.” Findlay remembers Reagon’s “insistence that music was a primary source for people’s history and meaning-making.”

reagon2.png

To be one in a number

THE LAST TIME I heard Sweet Honey in the Rock perform was at the opening events for the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., in 2018. Reagon retired from the group in 2003 and did not perform, but the sound she helped create resonated through the packed performance space. Rochelle Rice joined the ensemble in 2016, singing many of Reagon’s songs.

“The heavens opened up and it rained this huge torrential downpour,” Rice recalled in a recent interview with me over Zoom. “And I remember feeling how appropriate that these people are gathered here on this land with such rich history ... that there be this sort of baptism into a new era and a new history for this land.”

In 2020, amid worldwide protests in response to ongoing police violence against Black people, the refrain of “Ella’s Song,” a song Reagon wrote using the words of grassroots organizer Ella Baker, gained new voices. The refrain, “we who believe in freedom cannot rest,” circulated online and on picket signs as a new wave of activists joined the ongoing struggle.

Abena Koomson-Davis’ Resistance Revival Chorus recorded a version of “Ella’s Song” in June 2020. Koomson-Davis wrote this reflection: “I do not take the anchoring phrase ‘we who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes’ as a dismissal of self-care or some capitalist grind philosophy. It is not ‘I cannot rest,’ It is ‘WE.’ It is akin to the tradition of West African dance, drumming, and song, where the ‘WE’ generates continuous movement and music. While individuals and partners may take breaths between passages, our collective contributions keep the song of freedom playing.”

In “Ella’s Song,” the ‘we’ is important. I can rest, and you can rest, and together we can move forward.

A lesser-known verse of “Ella’s Song” reflects the kind of society and leadership Baker embodied and Reagon modeled. “Not needing to clutch for power / not needing the light just to shine on me / I want to be one in a number / as we stand against tyranny.”

Althoughshe won accolades — a MacArthur Fellowship, the Presidential Medal, and a Peabody to name a few — Reagon’s life reflected a commitment to collective liberation, not individual glory.

Sowing seeds

ONE OF REAGON'S last projects was an opera, Parable of the Sower, a collaboration with her daughter, musician Toshi Reagon. They co-wrote an adaptation of Octavia E. Butler’s novel with the same title. Many writers, activists, and theologians see Butler’s writing as prophetic. This past summer, Lynell George, author of A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia E. Butler, wrote an article for Alta Journal illustrating how “The Parable Is Now.” Butler’s parable begins on July 20, 2024. Reagon passed on July 16, 2024, just four days shy of Butler’s imagined time.

As 2024 draws to a close, we are living a truth that sometimes feels stranger than fiction. Reagon learned to sing from the voices of people who were born into slavery. The people who taught her learned from people who survived the Middle Passage. “It must’ve been incredibly difficult to be a woman — to be a Black woman — singing about justice and to hold so steadfastly to what she believed in and to stand up and align herself so clearly and firmly with all oppressed people,” Rice told me. “Right now, what we all need is courage to say the things that need to be said and to put our body in the places where it needs to be.”

I/we have the power to organize, gather, and speak truth to power. I/we can learn how to survive and thrive, to sing through the pain, and listen to the voices of those younger than me/us. In an NPR interview in July 2023, Toshi Reagon said the Parable of the Sower opera “is an invitation, just as Octavia Butler’s writing is: to imagine and create a different world.”

In the summer of 2023, I helped lead a day camp called Movers and Makers in the small rural Georgia town where I’ve put down roots with my family. Each morning, the campers learned about a person who made a positive difference in their community. For our morning circles, we would sing a modified version of Sweet Honey’s children’s song “Freedom Train.” This group of campers and leaders — Black, white, Asian, Latino, and multiracial — sang “It’s that freedom train a-comin’- comin’- comin’.” Each day we added the names of the people we had studied, and we sang, “This same train carried Bayard Rustin, Rustin, Rustin. It will carry you. It will carry you.”

We have a new name to learn and pass on. This same train carried Bernice Johnson Reagon, it will carry you. It will carry you.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!