Liberation is God’s intention. Liberation from all the spiritual, structural, and ideological shackles which bind and oppress -- is the promise of God’s salvation in history. The God of the Bible is about the creation of a new peoplehood who begin to experience the reconciliation, the justice, the healing, the wholeness, the fellowship that God wills to restore to men and women and to the entire creation. If liberation is so close to the heart and purpose of God, liberation must clearly be on the agenda of the people of God.

In addressing the question of liberation, the church faces a double danger. First, there is the constant tendency in the churches to withdraw to the private religiosity that spiritualizes liberation into personal piety, removes the gospel message from its concrete historical situation, and retreats into the contradictory religious experience that seems to deny the world while being totally conformed to its dominant values, structures, and ideological assumptions.

The other danger is to reduce the meaning of liberation to a particular political option, to equate it with movements and systems, and to replace one set of idols with another.

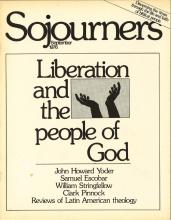

Both of these dangers are clearly evident in the present discussions and controversies surrounding the emergence of “liberation theology,” a movement born out of the experience of oppression especially in Latin America and elsewhere in the Third World. This is the subject of this issue of Sojourners.

Read the Full Article