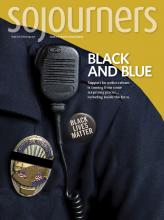

IN DECEMBER 2014, the white police chief of Richmond, Calif., showed up at a local protest against police brutality. The ethnically diverse city is infamous for its violent Iron Triangle neighborhood, but Chief Chris Magnus didn’t arrive at the protest to bust heads, or even to merely “keep an eye on” the assembly. Instead, he held a sign. It read, quite simply, “Black Lives Matter.”

The reaction was quick and intense—even the Richmond Police Officers Association issued a statement claiming Magnus had broken state law by “politicking” in uniform.

“I can understand how it is hard for a lot of police officers, especially given what has gone on in some of the protests,” Magnus said, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Nevertheless, he doesn’t regret holding the sign. “I’d do it again,” he said. “[T]he idea that black lives matter is something that I would think that we should all be able to agree upon.”

Like Richmond’s police officers denouncing Magnus, negative national reactions to the Black Lives Matter movement have come quickly and decisively, replete with slogans such as “All Lives Matter” and “Blue Lives Matter,” which refers to police officers.

Churches with “Black Lives Matter” signs have seen the word “black” defaced. Darren Wilson, the Ferguson police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown, received hundreds of thousands of dollars from online donors, as did George Zimmerman, the neighborhood-watch vigilante who killed Trayvon Martin.

In May, Louisiana took “Blue Lives Matter” to the next level when Gov. John Bel Edwards signed the “Blue Lives Matter” bill that added public safety workers to protected-class status for hate crimes legislation, thereby joining ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities. And in July, following the police shootings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and the sniper killing of five Dallas police officers, protesters in Baton Rouge were met with armored tanks, percussion weapons, and the threat of being charged with the “hate crime” of obstructing police in response to their nonviolent actions.

This is the politics of polarization. Discussions on race in the United States too often behave according to Newton’s third law of motion: “To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction.” It’s true within the church as well: While 82 percent of black Protestants believe that police killings are part of a pattern, 73 percent of white mainline Protestants say the opposite—to them, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, and the hundreds of other unarmed black Americans killed by police are “isolated incidents.”

Read the Full Article