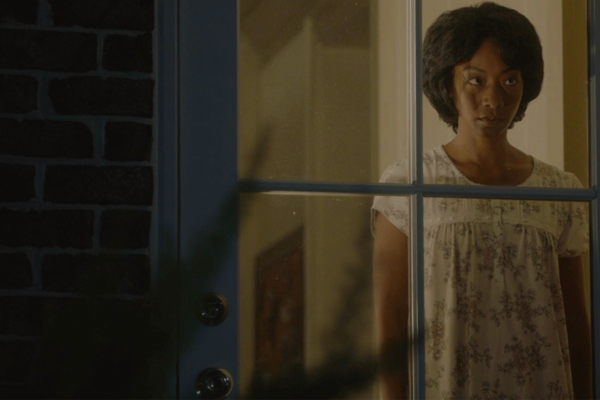

“I love the truth I find in dark films.”

In a 2003 speech titled “A Filmmaker’s Progress,” Sinister and Doctor Strange filmmaker Scott Derrickson, a Christian, made this statement in reference to spiritual and moral themes in his work. It’s an interesting idea to consider, not only because tales of terror get more popular this time of year, but also because Derrickson does most of his work in horror, a genre that doesn’t often get positive associations with faith.

Horror is typically considered exploitative, good for nothing more than the basest forms of gratuitousness that cinema can offer. But in fact horror is a smarter, more diverse genre than it’s given credit for. It is one of the best cinematic vehicles for social commentary.

Read the Full Article